» Talented Poor

» Affirmative Action

» Political Correctness

» Hispanic Antisemitism

» Jews & Immigration

» Bristol VA/TN

» About me

» Environmentalism

» Hobby Electronics

» Archive 1

» Archive 2

» Archive 3

» Archive 4

» Archive 5

» Archive 6

» Archive 7

» Archive 8

» Archive 9

» Local Crime 2

» Evolution Debate

» Progressives

» Immigration/Crime

» Liberal Racism

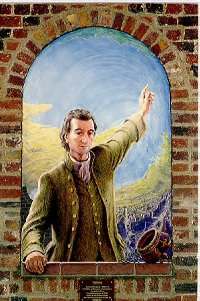

» James H. Lilley

» Honor Killings

Religion

- Deism

- Gnosticism

- Zoroastrianism

- The Devil in Judaism

- Pantheism

- Fundamentalism

- Evolution

- Original Sin

- Trinity

- End Times

- Apostle Paul

- Apostle John

- John Calvin

- St. Augustine

- Pelagius

- Martin Luther

- Jesus

- Unitarianism

- Christianity

- Judaism

- Paganism

- New Age

Religion of Peace

Koran: Form and Origins by Will DurantThe word koran (qur'an) means a reading or discourse, and is applied by Moslems to the whole, or to any section, of their sacred scriptures. Like the Jewish-Christian Bible, the Koran is an accumulation, and orthodoxy claims it to be in every syllable inspired by God. Unlike the Bible, it is proximately the work of one man, and is therefore without question the most influential book ever produced by a single hand.

In the year 633, when many of these men had died and were not being replaced, the Caliph Abu Bekr ordered Mohammed's chief amanuensis, Zaid ibn Thabit, to "search out the Koran and bring it together." He gathered the fragments, says tradition, "from date leaves and tablets of white stone, and the breasts of men." From Zaid's completed manuscript several copies were made; but as these had no vowels, public readers interpreted some words variously, and diverse texts appeared in different cities of the spreading Moslem realm.

Each passage taken separately fulfills an intelligible purpose, states a doctrine, dictates a prayer, announces a law, denounces an enemy, directs a procedure, tells a story, calls to arms, proclaims a victory, formulates a treaty, appeals for funds, regulates ritual, morals, industry, trade, or finance. But we are not sure that Mohammed wanted all these fragments gathered into one book. Many of them were arguments to the man or the moment; they can hardly be understood without the commentary of history and tradition; and none but the Faithful need expect to enjoy them all.

All the suras, except the first take the form of discourses by Allah or Gabriel to Mohammed, his followers, or his enemies; this was the plan adopted by the Hebrew prophets, and in many passages of the Pentateuch. Mohammed felt that no moral code would win obedience adequate to the order and vigor of a society unless men believed the code to have come from God.

Excerpts from Will Durant's The Age of Faith Pages 162-186 Pub. 1950

Religion and History[ Deism ] [ Gnosticism ] [ Christianity ] [ Judaism ] [ Zoroastrianism ] |