30 Years of Government Failure in Southwest Virginia

By Lewis Loflin

In Southwest Virginia’s job-scarce landscape, disability payments have become a lifeline—and a lucrative enterprise. Entire households often rely on multiple Social Security Disability (SSD) checks, supplemented by benefits like Medicaid, to make ends meet. Along Interstate 81 in Bristol, Virginia, billboards trumpet legal services specializing in securing these payments. Gene Cochran Attorneys at Law (276-676-2722) promotes expertise in “Personal Injury, Social Security Disability, and Workers’ Compensation,” a common refrain echoed across the region.

Local phone books reinforce this trend. Arrington, Schelin, & Herrell P.C. (276-669-9111) boasts “Confidential, Aggressive, & Experienced” representation for SSD and workers’ compensation claims, promising no fees unless successful (barring advanced costs). Massengill & Caldwell P.C. (423-764-1174) goes further, offering hospital and home visits—a stark contrast to the scarcity of medical professionals in the area. These firms thrive not on sleaze, but on the region’s economic reality: government checks often outpace wages from typical restaurant or retail jobs.

How pervasive is this reliance? In 2016, Census data highlighted stark contrasts: Virginia’s disability rate stood at 8.7%, West Virginia’s at 17.2%, and Tennessee’s at 12.8%. Southwest Virginia’s counties, however, far exceed these averages:

| County | Population (2016) | Disabled (2016) | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Russell | 28,557 | 7,759 | 27.1% |

| Scott | 22,706 | 5,372 | 23.7% |

| Smyth | 31,553 | 6,889 | 21.8% |

| Dickenson | 15,595 | 4,952 | 29.3% |

| Lee | 24,089 | 6,036 | 25.0% |

| Washington | 54,321 | 10,200 | 18.8% |

While exact 2025 figures for Buchanan and Wise Counties aren’t available, their profiles likely mirror neighbors Russell and Dickenson, given similar economic conditions. Washington County, the region’s wealthiest, still outpaces West Virginia’s state average in raw numbers. By 2025, factoring population decline (e.g., Buchanan County fell to 20,355 by 2020) and aging demographics, disability rates may hover near 30% in the hardest-hit areas.

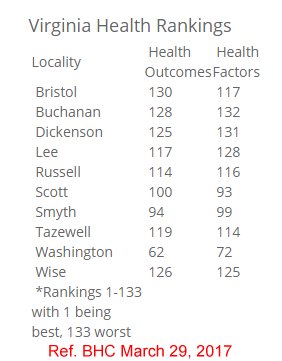

The health outcomes map above underscores a grim reality: Southwest Virginia ranks near Virginia’s bottom tier. In contrast, Tennessee’s Tri-Cities counties—Sullivan and Washington—fare better, often in the state’s top third, akin to Washington County, Virginia’s middling position. This disparity hints at a complex interplay: does poverty drive disability, or do disability claims reflect strategic adaptation to economic despair? The prevalence of legal ads suggests the latter—a system where disability is less a medical diagnosis and more a financial lifeline.

In Southwest Virginia, disability isn’t just a condition—it’s an industry sustaining families where jobs don’t.

Fast forward to 2025, and little has changed. The Social Security Administration reports a 2.5% benefit increase for 2025, raising the average SSD payment to about $1,600 monthly—still a boon compared to local wages averaging $12-$15/hour in retail. With over 60,000 jobs lost in Tri-Cities since 2009 (extrapolated from 2019’s 54,795 loss), disability remains a fallback. Adjacent Tennessee counties hover near 15% disability rates—above state norms but below Virginia’s Appalachian fringe. See Disability the Hidden Unemployment Program for deeper insight.

Acknowledgment: I’d like to thank Grok, an AI by xAI, for helping me draft and refine this article. The final edits and perspective are my own.