Gnosticism Introduction

Gnosticism, a shadowy strain of early Christianity, blends Hellenistic philosophy with Jewish and Christian threads, challenging orthodox narratives. Here’s its story.

In July 1209, the city of Béziers in southern France saw thousands slaughtered during the Albigensian Crusade, launched with Pope Innocent III’s blessing to eradicate the Cathars. Centuries earlier, in 537, Jews and Arian Ostrogoths in Naples had united against Catholic Byzantine forces, only to fall—outnumbered and fractured by internal divisions.

In the Languedoc, a prosperous and cultured region, Cathars and Jews found relative refuge, their literacy, and tolerance at odds with a Church that restricted vernacular scriptures and targeted dissent, paving the way for brutal repression.

Pope Innocent III aimed to crush the Cathar heresy—branded as the latest "Gnostic" threat—and found it deeply rooted across Europe. His support for the Cathar Crusade (1209–1229) laid the foundation for the Medieval Inquisition, formally established by later popes. Over the next five centuries, thousands faced torture and execution—often gruesome—for mere suspicion of heresy.

The Church's campaign against dissent, extended by Innocent's successors, also ensnared Jews through forced segregation and revived the spirit of earlier assaults on Arians, enforcing strict control over unauthorized vernacular scriptures beyond clerical oversight.

What fueled Christendom's rage and fear toward Gnostics, Arians, and Jews? From its formative years, Christianity grappled with Gnostic sects—denounced as "cults" of "secret knowledge" for their gospels offering insights reserved for the initiated—driving the Church to standardize its faith and scriptures to secure authority.

Arians, rejecting Christ's full divinity, and Jews, denying his messiahship, further defied this control, each challenging the Church's claim to universal truth and igniting centuries of fierce backlash.

Gnostic Cosmology and Theology

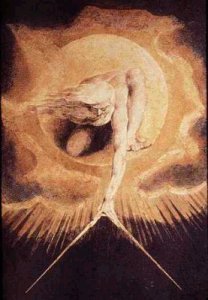

Gnosticism envisaged the world as a series of emanations from the highest "One" that produced a series of emanations. The lowest emanation was an evil god (the Demiurge) who created the material world as a prison for the divine sparks that dwell in human bodies. The Gnostics identified this evil creator with the God of the Old Testament and saw the Adam/Eve and the ministry of Jesus as attempts to liberate humanity from his dominion by imparting divine secret wisdom.

Gnostics, like Christians, take an allegorical view of the Old Testament. Gnosticism is loaded with Buddhism and other Eastern religious themes and draws heavily on Platonism.

Gnosticism pictured the cosmos as a descent from the supreme 'One' to the Demiurge—a flawed god who shaped the material world as a cage for divine sparks, equated by Gnostics with the Old Testament deity. They cast Adam, Eve, and Jesus as bearers of secret wisdom to break his grip, a vision steeped in Platonism and, as Elaine Pagels notes, resonant with Buddhist-like themes of transcendence.

I see Gnosticism not as a religion but a catch-all for 'heresies' the Church sought to erase—a campaign solidified after Constantine and Nicaea in 325 CE. In my view, Christianity leans more Gnostic than Jewish, a panentheistic blend forged in the Hellenistic crucible post-Alexander, merging clashing theologies into a tense unity.

Hellenistic Roots and Syncretism

From Greece to India in the 4th century BCE, Alexander's empire initiated a profound syncretism of philosophies and religious traditions. This vast dominion facilitated the westward diffusion of Eastern ideas and the eastward spread of Greek thought, creating a cultural matrix that persisted beyond his death in 323 BCE.

Within this Hellenistic milieu, Gnosticism emerged, taking full shape by 300 CE, though its origins trace back to the centuries between Greece's decline and Rome's rise. Scholars debate Gnosticism's roots: some see it as fundamentally pagan, arising from pre-Christian mysticism and later adopting Christian elements; others link it to Judaism, emerging from heterodox traditions of the Second Temple period; still others, as Elaine Pagels argues in The Gnostic Gospels, view it as a development of Jesus' teachings, a theological path as legitimate as the orthodox one, rooted in esoteric knowledge rather than institutional doctrine. Evident in its more refined theological systems is Gnosticism's deep debt to Platonism, which supplied its dualistic cosmology and concept of a transcendent divine realm.

This era aligns with the approximately 400-year silence in the Protestant Bible, from Malachi (c. 400 BCE) to Matthew (c. 4 BCE), a period the Apocrypha only faintly illuminates. I aim to explore Gnosticism's intricate ties to Christianity and Judaism, grounded in this transformative epoch.

Related Resources

- Gnosticism Resources, Definition, and Links

- Gnosticism as Explained by Bishop N. T. Wright

- Religious Syncretism and Christianity

- Alexander, the Jews, and Hellenism

- More on Alexander the Great, the Jews, and Hellenism

- Hellenistic Period After Alexander

- Alexandrian Philosophy and the Hellenization of the Jews

- Platonism and Christianity

- Demiurge Creator of the World

St. Augustine is the father of Western Christianity, both Catholic and directly connected to Martin Luther and John Calvin. He would give Western Christianity its theological excuse for murder and genocide against heretics such as the Gnostics, Arians, Donatists, etc. Oddly, his theology originates with the Gnostics. (Manichaeans)

- Quick navigation of this website:

- You Tube Channel

- Basic Electronics Learning and Projects

- Homepage

- Follow on X

- Skeptic Site

- Religion 1

- Religion 2

Acknowledgment

Acknowledgment: I’d like to thank Grok, an AI by xAI, for helping me draft and refine this article. The final edits and perspective are my own.