By Lewis Loflin

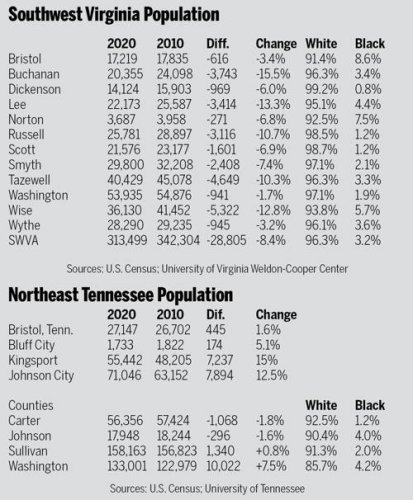

Fig. 1: Southwest Virginia lost another 8% of its population from 2010 to 2020.

Southwest Virginia’s population declined to 313,499 by 2020, a loss of approximately 29,000 residents since 2010 and possibly over 40,000 since 2000, despite hundreds of millions in public funds spent on job creation and economic development.

Social apartheid refers to de facto segregation based on class or economic status, where an underclass is separated from the rest of the population. In Bristol, Virginia-Tennessee, and much of Appalachia, this phenomenon is evident despite a predominantly white population (over 90%). Here, it manifests as economic disparity rather than racial division, though it’s often obscured by race-based narratives elsewhere.

The working class in the Bristol region faces challenges from both political parties: Democrats may overlook them due to race-class assumptions, while Republicans often prioritize business interests over worker welfare, exacerbating class divides. Government grants flow in, but public input is limited, and funds are frequently distributed through closed meetings, bypassing the broader community.

The Bristol Herald-Courier reported on August 21, 2021, citing a Chamber of Commerce study funded by an $81,000 government grant:

The Bristol Chamber of Commerce released a report detailing the Twin Cities’ biggest challenges and opportunities for economic growth. It highlighted an aging population, a "brain drain" of talented workers moving away for better opportunities, and low wages as key barriers to economic development.

These findings align with observations documented over the past 20 years. Bristol is split by the Virginia-Tennessee state line, with Bristol, Tennessee, in Sullivan County and Bristol, Virginia, in Washington County. The Tri-Cities area, including Kingsport and Johnson City, often encompasses Scott and Washington Counties in Virginia as well.

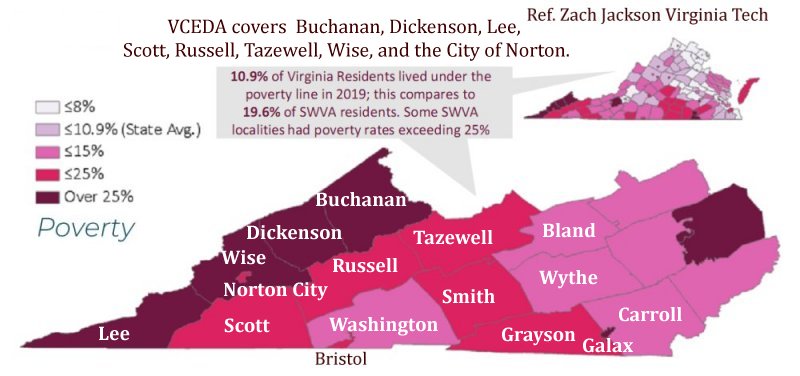

Fig. 2: Poverty Rates in Southwest Virginia

The Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority (VCEDA) works to stimulate economic growth in Southwest Virginia. While their efforts are commendable, relocating companies from one region to another does not equate to net job creation. For example, a company (renamed AJ Hubcaps for this article) closed its Pennsylvania facility, terminating 42 workers on May 20, 2022, and reopened in Southwest Virginia on June 14, 2022, with a $5 million incentive package. VCEDA reported 41 full-time employees at an average wage of $36,000 annually, though this figure lacks independent verification and may be optimistic.

According to Salary.com, the average production worker salary in Virginia was $39,906 as of October 2022, ranging from $35,784 to $45,168. Zach Jackson from Virginia Tech’s Office of Economic Development estimates the average full-time worker in Southwest Virginia earns $14,164 less than the state average and $9,162 less than the national average, suggesting a more realistic wage of around $26,000 without confirmed data.

VCEDA’s broader claims—such as 23,052 jobs "helped" by 291 projects from 1988 to 2018, per a CHMURA report—are questionable. Many promised jobs never materialized, and VCEDA acknowledges these are projections, not tracked outcomes. For instance, Travelocity’s multiple call centers in one facility were touted as creating 1,500 jobs, but never exceeded 200 at any time. Northrop-Grumman in Lebanon, Russell County, received $9 million in incentives but employed far fewer than projected, mostly in low-wage customer service roles.

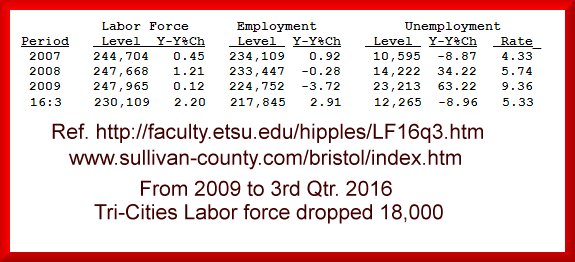

Fig. 3: Tri-Cities Labor Market Trends, 2007-2016

Data from Dr. Steb Hipple, a retired economist at East Tennessee State University, shows a significant labor force decline in the Tri-Cities area (Kingsport, Bristol, Johnson City) through Q3 2016. The labor force shrank by nearly 18,000, with a possible drop of 50,000 since 1990, though some recovery may have occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic. Low wages and limited worker protections contribute to this trend, often supported by local business interests.

The Ralph Stanley Museum in Clintwood, funded with nearly $2 million in public money, has not demonstrably boosted local employment or economic activity. Dickenson County’s population declined by over 10% since its inception. Similarly, Bristol Virginia Utilities received $5 million, including $2.2 million from tobacco funds, for fiber optic projects that duplicated existing infrastructure without adding jobs or customers.

Other examples include a $225,000 grant to a Bristol seafood restaurant and $1 million to a company promising 350 jobs but resulting in 600 layoffs. The Virginia Tobacco Commission has spent approximately $800 million with limited tangible results, often funding projects like horse trails or museums rather than sustainable employment.

Taxpayer cost: $8 million Bristol Virginia Energy Research Center remains unused. See Green Energy Project in Bristol Virginia and Biofuel Initiatives and Funding in Virginia.

Acknowledgment: I’d like to thank Grok, an AI by xAI, for helping me draft and refine this article. The final edits and perspective are my own.

Myself in the news: