Southwest Virginia Job loses 2010-2020.

Sullivan-County.com Homepage

by Lewis Loflin

Follow @Lewis90068157

On the web since 1998.

In 1997 I launched this website to protest the appalling job and labor climate in Tri-Cities. As long as one has outside income this place is great. For earlier material see Bristol Virginia Tri-Cities a Great Place to Retire 2018-19.

Southwest Virginia, etc. has been written off and marginalized for the same reasons as Baltimore - ruling class doesn't care.

I have documented extensively how government economic development programs never work. Their programs do not work with poor blacks in Baltimore. Their programs do not work with poor whites here. Enough said.

The Republican Party is hostile with American labor. They hate us and can't get enough foreign replacement workers to once again drive down pay scales. Both retiring Congressman Phil Roe and my Congressman Morgan Griffith voted to import millions more tech workers from India.

Quick navigation:

Science, education related subjects. This page.

Religious Traditions This page.

Violent crime in Virginia, elsewhere. (new page)

Common Sense Environmentalism (new page)

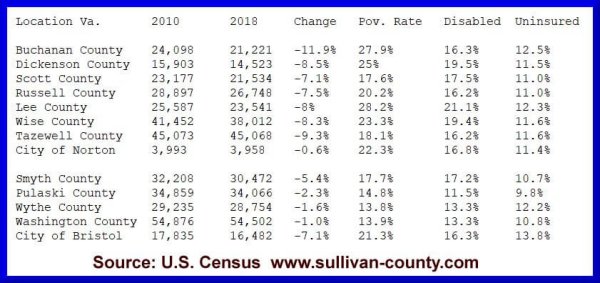

A study released by King University in 2016 notes the following:

Over the past several decades there has been a pronounced shift in the composition of personal income in the United States and in the regional economy – TriCities metro area and the Southwest Virginia coalfield region. A half-century ago, earned income accounted for 75-80 percent of total personal income. By 2014, the share of total personal income attributable to earned income had fallen to 57 percent in the TriCities and 50 percent in Southwest Virginia.

Economic Impact of Government Transfer Payments (PDF)

The problem is worse in the summer of 2022.

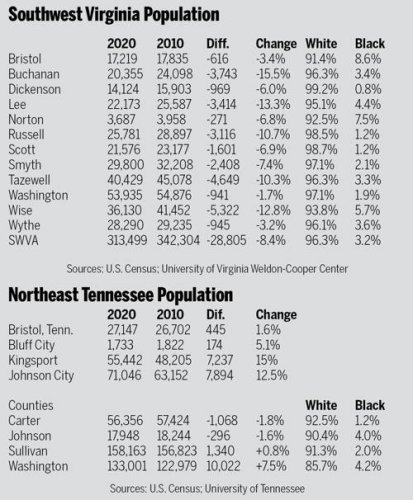

Southwest Virginia loses another 8% of its population from 2010-2020.

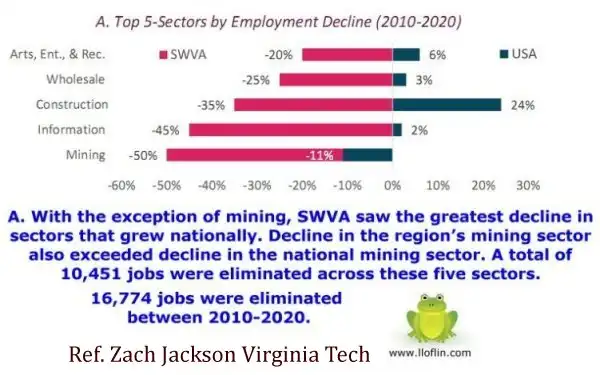

To quote Zack Jackson at Virginia Tech:

"Regional wages are not competitive with statewide and national wages. Turnover is high for low-wage jobs. SWVA residents disproportionately live in poverty; many workers cannot afford a basic standard of living."

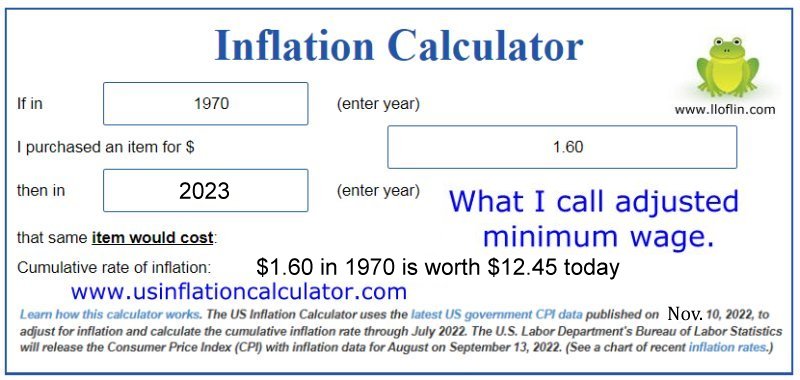

I refer to the adjusted minimum wage as $1.60 in 1970, adjusted for inflation in 2022.

The minimum wage in Virginia increased to $11 in January 2022. It is supposed to rise to $12 in January 2023.

Republicans are trying to stop the increase. Even $12 an hour September 2022 is still below inflation. Still worth less than $1.60 in 1970. It will be worth even less in 2023.

In general many jobs here run $2-$3 above minimum wage.

White People, Crime, and Welfare Myths

by Lewis Loflin

Follow @Lewis90068157

Most poor whites like poor blacks end up in poverty for the same reason: behavior. As of 2016 28% of white children were born to single mothers. There is a lazy, shiftless white underclass no different than the lazy, shiftless black underclass.

Not only out of wedlock births, but high levels of substance abuse, violence, sloth, etc. The press loves to play race, but it is class and behavior regardless of race.

In Southwest Virginia and East Tennessee massive drug busts can net as many as 20-50 people in one sweep, 90% white. We have 70-year-olds being busted for drug dealing.

43 People Arrested-Indicted for Drugs Spend Thanksgiving in Jail

This isn't 20-year-olds at least here. I averaged it to 37 or 38.

Conclusion: this is an overwhelmingly white problem clustered heavily around 30-45 age group located in or around public housing projects. Nearly all are of working age and if employed now (not likely), will be made more unemployable with a criminal record. Most employers already use drug tests and complain about the problems of finding employees in this region drug free enough to hold a job.

With little or no drug treatment available and even though these might be non-violent offenses, they often escalate to more violent offenses. That doesn't even account for the impact on children. Bristol according to reports has had a large uptick in crime clustered around, you guessed it, public housing.

This one is also a lot of fun in a sick way: Seatbelt Violation Leads to 14 Drug Arrests in Kingsport, Tennessee. This example includes multiple suspect engaged in all types of petty crime. 13 were white, one was black.

While I can't find the stats for just Southwest Virginia, we mirror closely West Virginia. To quote, "drug overdose death rates have increased in West Virginia from 36.3 per 100,000 in 2011 to 90.9 per 100,000 in 2021. Over the same period, drug overdose death rates increased from 13.2 to 32.4 per 100,000 in the U.S."

In study for the Virginia Government in 2016, "The Opioid Crisis Among Virginia Medicaid Beneficiaries" shocks even me. Please note the largest number of people in Virginia on welfare are white.

They note, "More broadly, at least 40,000 adults in Virginia's Medicaid program have a substance abuse disorder, and over 50% of Medicaid members with serious mental illness also have a substance use disorder."

And it gets worse, "More Virginians die each year from drug overdoses than motor vehicle accidents; Opioid prescriptions cost Medicaid $26 million annually; $28 million spent on ER and inpatient hospital treatment for Medicaid members with substance use disorders per year."

And, "Prescription opiate deaths are occurring statewide, especially in Southwest Virginia, Southside, Hampton Roads, Metro Richmond, the Shenandoah Valley, and Northern Virginia."

My County alone (Washington) suffered as many as 423 deaths CY2007-2014.

Download The Opioid Crisis Among Virginia Medicaid Beneficiaries PDF

"Americans Are Mistaken About Who Gets Welfare: People significantly overestimate how many African-Americans benefit from the most prominent programs."

Ref. Arthur Delaney and Ariel Edwards-Levy Feb 5, 2018, Huffington Post

Politifact or Politicrap claims 39 million people live in poverty, and whites make up 43% or ~17 million, thus are not the majority that live in poverty. Wrong, whites are by sheer numbers, not percentages. We also need a more realistic measurement of poverty.

The Huffington Post breaks this down. To quote, "Medicaid had more than 70 million beneficiaries in 2016, of whom 43 percent were white, 18 percent black, and 30 percent Hispanic."

Medicaid is the most extensive poverty program by far. 43% of 70 million is 30.1 million whites. In 2020 47.2 million Americans were black. By the numbers, poor whites are ~64% of the entire black population.

The white population in 2021 is ~252 million, with ~30 million in poverty is ~12%, far higher than the 8% given elsewhere.

In Southwest Virginia, 50% of the households live on government transfer payments. We are ~90% white.

By Medicaid use, there are ~2.4 times as many poor whites as blacks.

To quote, "Of 43 million food stamp recipients that year, 36.2 percent were white, 25.6 percent black, 17.2 percent Hispanic, and 15.5 percent unknown." The 15.5% is troubling. Of 43 million recipients, ~15.6 million are white, and ~11,000 million are black—again, far more poor whites than poor blacks or Hispanics.

Because there are far more poor whites than poor blacks or Hispanics, they get more welfare. The Huffington Post is correct on the public misconception of poverty and welfare use. However, the press pushes the false narrative that only blacks and Hispanics live in poverty.

Poor whites as a percentage are smaller than the total white population.

- 58 White People Sentenced to 348 Years Over Methamphetamine

- Impaired Driver Faces Felony Drug Charges in Johnson City

- Another 48 People Nailed in Bristol Virginia Drug Bust

- Black Gang Arrested for Rape Laugh at Judge

- Break Light Leads to Drug Bust for Black Male

- Missing License Plate Lands Stupid Man in Jail for Meth

- Seatbelt Violation Leads to the Arrest of 14 People on Drug Charges

- Black Versus White Crime in Missouri

- How Government Exported Black Crime into Ferguson Missouri

- Mother and Son jailed for Drugs in Washington County, TN

- Three Feral Whites Accused of Double Murder over Drugs, Money

The press claimed Terry McAuliffe and local politicians claimed 400 new jobs. They lied, gave away millions.

To this day the press has never corrected this story. See 400 New Jobs is Just Zero Jobs

How could they spend millions on jobs and economic development and lose almost 29,000 residents?

How can spending millions on transportation and other economic development funds for an abandoned train station be rational? No trains run today; 15 years later, the building is still empty.

See Bristol Trainstation Still Empty 2022.

How do horse trails and horse camps facilitate transportation? Spending transportation funds on this is either irrational or simply fraudulent.

Washington County, Virginia, says this is about economic development, which isn't about jobs for those that live here:

"Economic development does not necessarily mean growth, although the growth of both population and revenue may be a result. Economic development means strengthening the community's economic base or the part of the local economy that brings in money from outside the county."

In reality, the money goes to the "haves" that control where it goes and who benefits.

Spending over $140 million on clean energy "research" centers results in empty buildings. Great for consultants, contractors, and their friends.

What is social apartheid? What does that have to do with Bristol, Virginia-Tennessee? Or Appalachia in general?

Some define this as "Social apartheid is de facto segregation based on class or economic status, in which an underclass exists separated from the rest of the population."

They discussed race as a diversion, where the population is 90% plus white. For that reason, the working class in the Bristol region faces hostility from Democrats for race plus class and Republicans' rabid pro-business anti-worker attitudes, plus class warfare.

Millions flow in from government grants, etc. Still, the general public is barred from the input process and locked out of government meetings. When disbursing public money, doors are locked.

The Bristol Herald-Courier, August 21, 2021, notes the following report from our Chamber of Commerce, paid for by an $81,000 Government grant:

BRISTOL, VA. -- The Bristol Chamber of Commerce on Wednesday released a report detailing the Twin Cities' biggest challenges and opportunities for economic growth... The report cited an aging population, the "brain drain" effect of talented workers "moving away to seek better employment opportunities" and low wages as some of the area's top barriers to economic development...

Darn, they dare mention low wages, something they have fought to maintain for years!

No kidding, the very things I documented here for over 20 years without a government grant to waste.

Note that Bristol is cut in two by the Virginia-Tennessee state line. Bristol, Tennessee, resides in Sullivan County, Tennessee, Bristol, Virginia, and Washington County, Virginia.

Often referred to as Tri-Cities centered around Kingsport, Johnson City, and Bristol. It usually includes Scott and Washington Counties, Virginia.

Popular pages:

- Environmentalism 50 Years of Observation

- Bob Jones University Racism, anti-Catholic Accusations

- Christian-Newsom Murder Trials Rocks Knoxville

- Murdering Mother The Hidden Face of Honor Killing

- Preacher Combs, Wife Sentenced 179 Years in Prison

- Sullivan County, Tennessee Strip Bars Wars

- Corporate Welfare, Red Lobster, Bristol Virginia

- What is Gnostic Demiurge? Christian Heresy

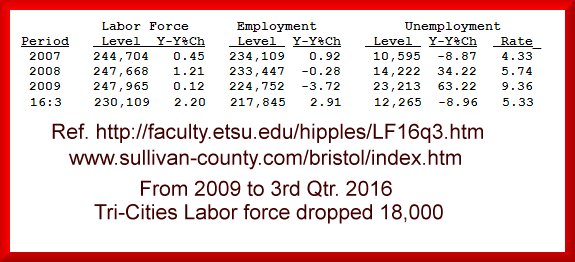

Update September 3, 2019. Based on data from Dr. Steb Hipple, an economist at East Tennessee State University (retired), his data goes to the 3rd Quarter of 2016. The level of job losses in Tri-Cities is staggering.

The Tri-Cities Consolidated Statistical Area comprises Kingsport, Bristol, Johnson City, and surrounding counties.

The Bristol Virginia-Tennessee, Kingsport, and Johnson City Urbanized Area Labor Market lost thousands of jobs shrinking the labor force that shrank unemployment rates. The above table shows a decline in the labor force by almost 18,000.

Since 1990, the labor force may have dropped by 50,000. It may have recovered some since 2016 except for the coronavirus pandemic.

The Chamber of Commerce that owns local politicians fights hard to keep pay low, unions, and worker protection out.

Politicians fight anything that benefits workers but can't pull out the public checkbook fast enough to fund corporate welfare and waste.

Poverty and low pay become a business asset and source of pride. It is related to statements such as this from local politicians:

"high unemployment can be an advantage because it increases the number of available workers...Our labor force is a huge advantage since the county unemployment rate is twice the state average, and regionally, the unemployment rates range from 3.5 percent to 15 percent..."

Or this statement from a man whose company received $10-$20 million in public subsidies to create 120 jobs, then filed for bankruptcy and left:

"It's a little-known fact that roughly 20 percent of the children in Southwest Virginia live below the poverty line and go hungry every night."

Kevin Crutchfield, President Alpha Natural Resources, January 15, 2009, in Abingdon, VA.

The Alpha Fiasco

Alpha Natural Resources filed bankruptcy after a multi-million dollar public incentives deal.

A sale involved selling their office building in Abingdon to Washington County. They paid millions over the appraised value—a deal done behind closed doors, like everything else.

They agreed to build a new headquarters building in Bristol, Virginia.

Then Alpha received $10-$20 million worth of land, kickbacks from the local utility, and State grants. They promised 120 new jobs and would retain even more.

Politicians claimed hundreds of new jobs. Companies not relocating or moving within the same community is job creation.

The "hundreds" of new jobs were a myth. Those "new" jobs never existed. Alpha filed for bankruptcy. They sold the building for $28 million in 2015. That was about the worth of the public money they received.

The developer pocketed the money, and Alpha moved their office across the state line. Now years later, their building is still empty.

Their corporate headquarters is now 340 M.L.K. Jr Blvd, Bristol, TN 37620.

Abingdon, Virginia, is the County seat for Washington County.

As a Washington County resident, I protested against the Alpha Building purchase.

They spent $2 million over appraised value. Plus over $1 million in renovation costs, plus millions in interest.

We already owned more than sufficient county office space.

One BOS member claimed this was part of the overall Alpha incentive deal.

I also warned those jobs would never materialize. That level of public funding in a failing industry (coal) was foolish.

I was proven right.

- Gov. McAuliffe Another Porkbarrel King

- 400 New Jobs is Just 0 Jobs

- Bristol Schools to Teach Cannabis Farming?

- Bristol Compressors Stabs Workers-Taxpayers in the Back

- ALICE in Poverty Land in Southwest Virginia

- Morgan Griffith, Phil Roe Betray American Workers

- Morgan Griffith Wrong about Volvo Trucks

- Tri-Cities Labor Market Report 2011 & 2016

- Taxpayer Funds Wasted To Renovate St. Paul Hotel

- Gov. McAuliffe Clueless on Jobs But Not Pork

- ARC Virginia Grants Pork and Salaries 2015-16

- 30 Years of Failure in Southwest Virginia

- Exide to Rehire 40 Bristol Workers - Not After All

- Disability Still Big Business 2017 in Southwest Virginia

- Disability the Hidden Unemployment Program

- $6 Million Bristol Trainstation 2022 Still Producing Nothing

- Appalachian Regional Commission is a Waste

- Address Corporate Culture Before Handing Out Money

- Nicewonder Property Fiasco in Bristol, Virginia

- Blogging sites (this one) in the news

- Local activist working to help displaced trailer park residents

- A Town's Future Is Leaving the Country LA Times

- My letters printed in the Bristol Herald Courier

- Sullivan County Commission Threatens to Sue Activist Over Free Speech

- Sullivan County, Tennessee Religious Wars 22 Years Later

- Job Horror Story Tri-Cities 2002, 24,000 Jobs Lost

- Crony Capitalism and more Lousy Call Center Jobs

- How Cable Ready Socialism Failed Southwest Virginia

- Congressman Boucher Brings Home the Bacon in 2009

- Bristol Virginia Utilities Update for 2009, 2019

- Congressman Boucher's Failed Call Center Legacy

- More Replacement Call Center Jobs for Scott County Virginia

- Wise Virginia Call Center Won't Hire 500 New Workers

- Three Decades of Job Losses in Southwest Virginia

Quick navigation of science related subjects this page:

- Electronics, Nuclear Reactors, Applied Science

- Critical Look at Islam and Religion

- Environmentalism Article List

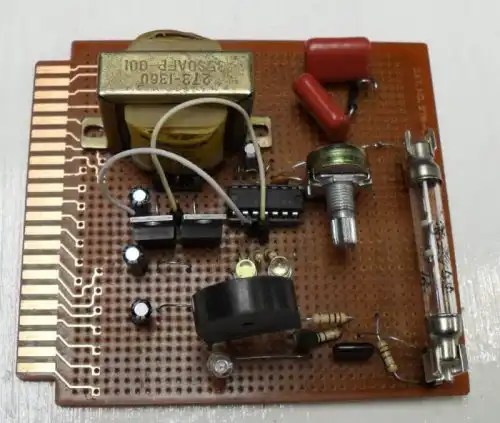

Home built Geiger counter project.

Electronics, Nuclear Reactors, Applied Science

The above banner is to my electronics projects website. My interest is applied science and technology. That is what I will cover moving forward.

In Southwest Virginia, there is a discussion of placing small modular nuclear reactors in the region. I have a section on Geiger counters and even built my own.

Virginia has one of the larger uranium reserves in the US. They have blocked mining it because of pollution concerns. I can't blame them. But we constantly offshore pollution in the name of climate change.

We need to replace most fossil fuels. We have the ability right now to replace all coal, natural gas, and bio-fuels for electricity today. Windmills and solar panels are a massive waste of resources, leaving millions of tons of toxic waste from manufacturing and mining.

See Green Technology Highly Polluting, Environmentally Destructive (Off site)

I'll be exploring issues on nuclear reactors they could place in Southwest Virginia. I'll present the material in more layperson's terms. We have, I'd estimate, one million tons of potential nuclear fuel in storage we can use without creating more pollution mining it in developing countries.

The dangers of nuclear radiation are overblown. It occurs naturally in the environment, our blood is radioactive, and sites where nuclear testing and reactor meltdowns have become nature preserves. These areas are full of plants and animals.

Environmentalists oppose the only viable solution to reducing CO2 because CO2 has never been the issue. They want to remake society by promoting some Green Eden mythology or outright communism. Often a combination of both.

Too many consider any artificial substance dangerous to the natural world, so pristine nature is the intrinsic good. Some introduce spiritual and religious aspects into this. Some go as far as viewing humanity as evil, placing untouched nature above human welfare.

Artificial sources of radiation are no different than natural sources. The claim is any radiation exposure is deadly. This claim has been disproved.

It is provable because millions live in areas with high natural background radiation levels with no measurable ill effects. We are immune to low-level sources, natural or artificial.

I'm not going into how most environmentalists are evil. But far too many extremists occupy government and academia. Their positions are incoherent and contradictory, even anti-human. And they hurt the environment.

See Ominous Parallels Environmentalism, Collectivism by Erich Veyhl.

Let us explore real-world examples.

- These links are on my electronics website.

- My Geiger Counter Project

- CD4047 Monostable Multivibrator Circuit

- Geiger Counter and Radioactivity

- Introduction to Geiger-Mueller Counters and Electronics

- Getting Real About Radiation Myths and Hazards

- Uranium Hype-Facts and Virginia Uranium

- Uranium Basics and Isotopes

- Climate Change and Volcanoes

In a high tech age that has seen the creation of artificial intelligence by computers, we are also seeing the creation of artificial stupidity by people who call themselves educators. Thomas Sowell

From Encyclopedia Britannica on Postmodernism:

Postmodernism, also spelled post-modernism, in Western philosophy, a late 20th-century movement characterized by broad skepticism, subjectivism, or relativism; a general suspicion of reason; and an acute sensitivity to the role of ideology in asserting and maintaining political and economic power.

- Environmentalism as Religion by Michael Crichton

- Religious Fundamentalism Explained by Michael Crichton

Related see The Nazi Roots of Multiculturalism

To quote Patrick Moore co-founder of Greenpeace:

The collapse of world communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall during the 1980s added to the trend toward extremism. The Cold War was over and the peace movement was largely disbanded. The peace movement had been mainly Western-based and anti-American in its leanings. Many of its members moved into the environmental movement, bringing with them their neo-Marxist, far-left agendas. To a considerable extent the environmental movement was hijacked by political and social activists who learned to use green language to cloak agendas that had more to do with anticapitalism and antiglobalization than with science or ecology

- Climate Fall of the Late Roman Empire

- End of the Vikings in Greenland

- Lost Colony of Roanoke Island

- Whale Fossils Show Ice Free Arctic

- On Bristolblog website:

- Diversity Destroyed Aurora Colorado Schools

- Who are the Smartest Countries? Nobel Prizes Tell the Story

- Why Learning Programming is Difficult

- Institutionalized Liberal Failure

- What Level of Knowledge for Technology?

- Intelligence Predicts Economic Social Outcome

- Why Many People Shouldn't Get a 4-Year Degree

- How Progressives Ruin Education

- Michigan Education Ruined by Diversity

- Western-American Culture is Superior - Get Over It

- Scientific Advances Built on Western Culture

- Baltimore Schools Another Diversity Failure

- Black Boys Can't Read in California

- On this website:

- California Merit Based Immigration Needed for Hispanics

- Michigan Proves Merit Based Immigration Needed for Muslims

- Slaves Never Built America - Slavery Ruined the South

- Unhappy Facts Black Slavery, Lynchings in the U.S.

- Majority of Poor Americans are White

Mahsa Amini murdered by Islamic fundamentalists.

Critical Look at Islam and Religion

While many individual Muslims are fine people, its culture and religious precepts are barbaric as public policy. The culture of Saudi Arabia, etc., is unacceptable in a civilized nation.

I apply the same skepticism to other religions. The problem with Islam is the fusion of religion and politics. This fusion of Islam and state may not be true for individual Muslims - then I have no problems at all.

Because of immigrant and Muslim criminals and gangs Sweden suffers daily bombing attacks. So far there are claims of 18 bombings in 2023 as of 1/17/2023. Third-world immigration is death and destruction in advanced societies. To quote,

"In Stockholm county alone, 126 shootings were recorded in 2022, resulting in 28 deaths, as well as 31 attacks with explosives, which was up from 23 deaths as well as 25 attacks with explosives in 2021. Countrywide, Sweden saw 388 shootings resulting in 61 deaths and 90 attacks with explosives last year; the number of deaths was up by one-third over the previous year."

Source: www.politico.eu January 12, 2023.

Let me get several issues out of the way:

Islamophobia does not exist. Islamophobia is a manufactured term to attack critics of Islamic politics. The far-left tries to use Muslims to attack the system while grooming their children into sexual perversion.

Muslims in Dearborn, to their credit, put a stop to peddling sex in public schools.

To me, to be pious is not fundamentalism.

I classify all religious fundamentalism carried into politics as extremism.

Islam is not a race or even ethnicity any more than Christianity is a race or ethnicity. Many Muslims are as white as I am.

The Islamic faith is not monolithic. While the two main sects are Sunni (majority) and Shia, several smaller groups, such as the Ahmadis, also exist. The Ahmadis face terrible persecution from other Muslims.

Muslims are not victims, but Islam has exterminated every people and culture from North Africa to China. Millions were murdered or forcibly converted. Muslims today are not responsible for this, only what they do now.

Muslims in Africa sold non-Muslim blacks into slavery. Slavery was widespread in the Ottoman Empire. Two million whites were taken as slaves by Muslims.

Europeans and whites ended slavery in many cases going to war with Muslims to do it. To quote,

Paul Fregosi in his book Jihad in the West: Muslim Conquests from the 7th to the 21st Centuries calls Islamic Jihad "the most unrecorded and disregarded major event of history. It has, in fact, been largely ignored," although it has been a fact of life in Europe, Asia and Africa for almost 1400 years.

As Fregosi says, "Western colonization of nearby Muslim lands lasted 130 years, from the 1830s to the 1960s. Muslim colonization of nearby European lands lasted 1300 years, from the 600s to the mid-1960s. Yet, strangely, it is the Muslims...who are the most bitter about colonialism and the humiliations to which they have been subjected; and it is the Europeans who harbor the shame and the guilt. It should be the other way around."

I consider Saudi Wahhabism (violent Sunni fundamentalist) and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood (Sunni Marxist) as terrorist-hate groups.

That is for the same reasons I consider secular humanist BLM (racist, Marxist) and Antifa (racist, Marxist) terrorist-hate groups.

So I say this to my Muslim brothers and sisters: a critique of religion is a right. There is no right to demand pandering or special accommodations.

Free speech is a right, get over it.

- Murdering Mother Hidden Face of Honor Killing

- Making Fun of Islam is Not a Hate Crime

- Deism Versus Islam An Overview by Lewis Loflin

- Why Muslims Can't Build a Lightbulb by Lewis Loflin

- Deist Examination of Islamic Trinity by Lewis Loflin

- Chronology Early Islam Historical Perspective by Lewis Loflin

- Mythical Golden Age of Islam

- Koran Origins by Ibn Warraq

- Mohammed the Man Islamic Ideology by Lewis Loflin

- Mythical Prophet of Early Islam by Lewis Loflin

- When Christianity Pushed Back Muslim Attacks

- Islam the Demise of Classical Civilization

- Europeans Victims of Muslim Colonialism

- Barbary Pirates Muslim Slavery Industry

- Muslim Terror in the Balkans

- Myth of Colonialism and Science

- Muslim Wars Against Abyssinia (Ethiopia)

Most popular May 2023. Note the religious material is from a historical, cause and effect perspective.

- Apostle Paul Founded Christianity

- Guestbook Archive

- Overview Classical Deism

- An Overview Gnosticism and the Bible

- Elizabeth and the Puritans by Will Durant

- Origins Christianity 101

- What is the Gnostic Demiurge?

- Exploring Religion Modern and Ancient 1

- Jesus the Man Before Paul's Christ

- Religious Syncretism, Hellenism, and Christianity

- At the Origins of English Rationalism

- An examination of Pelagius Why He was Right

- Judaism Meets Zoroastrianism

- Why did the Apostles Reject Paul?

- Neoplatonism Relationship to Christianity, Gnosticism

- Origins of Christianity 101

- Gnostic Demiurge Creator of the World?

- Apostle Paul Founded Christianity

- Why did the Apostles Reject Paul?

- Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

- Another Look at Pelagius - Cleared of Heresy

- Pelagius Why was Right

- Classical Deism

- Deism

- Gnosticism

- Zoroastrianism

- The Devil

- Pantheism

- Fundamentalism

- Evolution

- Original Sin

- Trinity

- End Times

- Apostle Paul

- Apostle John

- John Calvin

- St. Augustine

- Pelagius

- Martin Luther

- Jesus

- Unitarianism

- Christianity

- Judaism

- Paganism

- New Age

- Web Master

- Hobby Electronics

- Environmentalism

- US Constitution

- Religious Themes

- Archive 1

- Deism

- Gnosticism

- Apostle Paul

- Bristol VA/TN

Environmentalism Article List

- Killing Children - Nature has Rights

- How Ecological Homeostasis and Hysteresis Regulate Climate

- Environmentalism as Religion by Michael Fumento

- Environmentalism's Fear-Loathing of Technology

- Ages of Gaia Writer James Lovelock Sounds an Alarm

- Writer James Lovelock Backtracks on Revenge of Gaia

- How Bacteria Created Natural Nuclear Fission

- Environmentalism as Religion by Michael Crichton Part 1

- Environmentalism as Religion by Michael Crichton Part 2

- Shockingly Rapid Climatic Shifts are Real

- Hypsithermal Warming Spreads Civilization 6000-9000 BC

- Dr. James Hansen Paid Environmentalist

- NASA Scientist Demands Prosecution Climate Change Critics

Repeat of 2012 Energy Fiasco

To quote one source:

"Average crude oil prices in 2012 were at historically high levels for the second year in a row. Brent crude oil averaged $111.67 per barrel, slightly above the 2011 average of $111.26. West Texas Intermediate oil averaged $94.05 per barrel in 2012, down slightly from $94.88 in 2011."

Oil prices hit $147.02 on July 11, 2008. Thus began an orgy of pork-barrel waste.

High energy prices combined with the 2008-9 housing bubble opened the door to government money.

Virginia politics drowned in a corrupt system of public-private partnerships.

Billions flowed for "green" energy research, biofuels, and university grants. Private business interests working in secret with economic developers pocketed millions.

Every effort failed. Because of government wars on fossil fuels, we are back to 2012.

Politicians and their business associates will pour billions down a green rathole.

In Southwest Virginia, we face a bleak future. The working poor that dominates the region will face higher energy and food prices.

Not just higher gas prices, but electricity costs as well. The Northern Virginia Climate Thumper cult demands more costly "renewable" energy sources.

I warned about this in 2010, and was proven right.

(Above) Taxpayer waste $8 million Bristol Virginia Energy Research Center another empty building producing nothing.

- Virginia's $140 Million Green Energy Boondoggle

- Biofuel Scams Wastes Millions in Virginia

- NanoChemonics Fiasco in Wise, Virginia

Yes we have broadband and spent millions.

A look at 2 decades of cable ready socialism in our region:

Cable Ready Socialism

How CGI-AMS and Northrop Grumman Failed Russell County

How Cable Ready Socialism Failed Southwest Virginia

Sprint Jumps State Line Collects Millions

U.S. Solutions Dumps Bristol Virginia for Bristol Tennessee

Travelocity Fails Dickenson County

Creating real jobs or raising the standard of living for workers, the priority is the opposite.

In fact, a so-called "futurist" came to Tri-Cities at the behest of business leaders to sell the idea. He gave a speech in Kingsport. Ed Barlow of "Creating the Future"

Quoting March 4, 2004, Kingsport Times-News:

"A significant component of your economic future in Sullivan County is recruiting Hispanics, making sure they get highly educated and integrated into the community. ... They can fill all of the various job categories you have. The future economic vitality model is based on the back of a well-educated, ethnically diverse work force..."

Comment: what in the heck do illiterate, unskilled Hispanics have to do with "well-educated" working minimum wage jobs? They imported thousands of illegal alien Hispanics into nearby Morristown and Hamblan County, Tennessee, with double-digit poverty rates. More here...

Exide Fires Bristol Workers - Received $34 Million in Stimulus Funds

In 2009 Exide announced the firing of 567 workers at its Bristol battery plant. That was 70 percent of its workforce.

Opened in 1994, Exide's Bristol plant is a manufacturing and distribution center for lead-acid batteries used in the automotive, marine and specialty industries.

They had 817 employees at the time. They did some rehires that were proclaimed "new jobs."

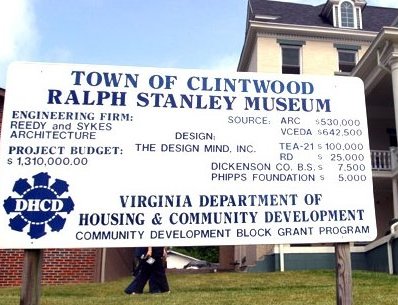

Typical is the almost $2 million Ralph Stanley Museum that failed, and was taken over by the Town of Clintwood.

My sister lives there and there is no evidence this project brought jobs, etc. to Clintwood.

It is still there today. It is closed but supposed to open this spring in 2022.

Their website is ralphstanleymuseum.com.

Why didn't Ralph pay for his own house?

Note Dickenson County has lost another 10% or more of its population since this opened. This museum is simply a gimmick in my view to funnel government grants.

See Looking back at the waste of Virginia Tobacco Funds.

I wrote the following and stand by it today. In 2022 these efforts have produced little, if anything.

Printed Kingsport Times-News January 10, 2005

Re: Virginia Tobacco Funds (December 6) the Times-News has missed the mark. These funds that should have gone for education, health care and economic development have become a ready source of fraud and waste for local Southwest Virginia governments.

This has produced nothing in the way of real jobs or helped the common people.

Tourism doesn't create good jobs, if at all. My relatives in Wise, Dickenson, and Russell Counties know of nothing any of these museums have brought in.

Carter's Fold near my home, has been given over $500,000 in government grants and hasn't produced a single job.

Bristol Virginia Utilities has received about $5 million in taxpayer funds (about $2.2 million in tobacco funds) touting fiber optics as job creation.

In one case they admitted running lines to areas they knew would never produce anything, then kept half the grant ($350,000) for expenses.

All they did was overbuild existing fiber optic infrastructure and have not connected a single customer that didn't get services before. After running up a whopping $50 million in external debt, they have failed to create a single job or bring in a single new business two years later.

Now Bristol, Tennessee is prepared to commit the same stupidity, while Bristol, Virginia has the highest electric rate in Tri-Cities.

Another $225,000 went to a seafood restaurant in Bristol. ($175,000 was EDA grants; $50,000 from Bristol Virginia Utilities.)

Another Bristol company received $1 million ($500,000 Tobacco Funds) to create 350 "new jobs," but instead we got 600 lay-offs.

The company kept the money. Washington County gave away $40,000 for a non-profit retirement community study that produced nothing.

As for Joy Manufacturing in Duffield, explain why they closed their facilities in Washington County, Virginia, industrial parks at the same time. The net result was a loss of over 100 jobs and millions in losses to taxpayers.

It's time to stop the waste and use tobacco grants for what they were intended for.

Lewis Loflin

Bristol, VA

- Food City Gets $6 Million Corporate Welfare

- Istobal USA Moves to Bristol Virginia Success!

- Bristol Compressors Cuts Another 250 Jobs

- $2 Million Wasted at Virginia Intermont College

- Welfare - Not Just Poor People

- Bristol Tennessee job fair 2012

- Smith County Loses Another 300 Jobs

- Alpha Building Fiasco 2022.

Sprint Back-Stabs Bristol Virginia

"We didn't see it coming" says confused Bristol, Virginia leaders.

Here is another example of one low-wage community trying to outbid the neighboring low-wage community at taxpayer expense for low-paying jobs.

Sprint has turned down a lucrative corporate welfare package from Bristol, Virginia, and will jump the state line to Sullivan County.

See Sprint Moves to Sullivan County.

Crony Capitalism Comes to Wise County, Virginia

Lieutenant Governor Bolling along with local economic development hacks are having a pork party in Wise County.

Republicans scream about government waste with President Obama and his failed stimulus plan.

They call it waste, but do the very same thing.

In this case, three private sector startups got almost $9 million in corporate welfare, largely repeating earlier failed efforts at the same thing.

Nothing is known to have come of this deal.

We must ban government funding for private business ventures. Restore real free enterprise free of government money.

- Washington Post Exposes the Grundy Fiasco

- Taxpayer Funded Wal-Mart Opens in Grundy, VA.

- Grundy Virginia and the $200 million Bridge to Nowhere

- A Look at the Corporate Progressive Alliance

- Poor People in Virginia and Tennessee are White

- A Suggestion for Reform in Southwest Virginia Won't Happen

- How "Closed Session" Betrays the Public Trust

- Exide Dumps Bristol Workers after Receiving $34 million in Stimulus Funds

- Sprint Dumps Bristol Virginia for Bristol Tennessee

- Crony Capitalism Times Three Comes to Wise County

- Barter Theatre Money Woes Exposes Tourism Hype

- Barter Theatre Panics Over Cuts in Government Largess 2011

Below is more proof and the last I'll write on this subject. Morgan Griffith is my congressman VA 9th. Phil Roe represents East Tennessee 1st and is retiring. They are worthless.

- Bristol Compressors Stabs Workers-Taxpayers in the Back

- ALICE in Poverty Land in Southwest Virginia

- Morgan Griffith, Phil Roe Betray American Workers

- Morgan Griffith Wrong about Volvo Trucks

- Illegal Aliens Hurt Poor Tennessee Workers

- Virginia Tobacco Commission Loses $1.1 Billion

- 400 New Jobs is Just 50 Jobs

- Why the Poor are a Goldmine

- The system, Income, and Education in Bristol VA/TN

- Where the Welfare Millions Go in Appalachia

Taxpayer waste $8 million Bristol Virginia Energy Research Center another empty building producing nothing. See Green Energy Boondoggle in Bristol Virginia and Biofuel Scams Wastes Millions in Virginia.

Update July 2017: I warned about Nulife Glass and predicted it was a scam. In June they fired the few people they hired and left Bristol with between 20-30 million pounds of CRT glass - glass loaded with lead. Press reports claim Bristol is trying to sue the company but likely will get stuck with disposal. They sold a $1.3 million building for less than $200,000 and half of that was payed for by grants.

- Tri-Cities Labor Market Report 2011 & 2016

- Taxpayer Funds Wasted To Renovate St. Paul Hotel

- Gov. McAuliffe Clueless on Jobs But Not Pork

- ARC Virginia Grants Pork and Salaries 2015-16

- 30 Years of Failure in Southwest Virginia

- Exide to Rehire 40 Bristol Workers - Not After All

- Disability Still Big Business 2017 in Southwest Virginia

- Disability the Hidden Unemployment Program

- Bristol Trainstation 2017 Still Producing Nothing

- Appalachian Regional Commission a Waste

- Address Corporate Culture Before Handing Out Money

- Your College Degree Worthless in Tennessee

Update July 2017: I warned about Nulife Glass and predicted it was a scam. In June they fired the few people they hired and left Bristol with between 20-30 million pounds of CRT glass - glass loaded with lead. Press reports claim Bristol is trying to sue the company but likely will get stuck with disposal. They sold a $1.3 million building for less than $200,000 and half of that was payed for by grants.

Four East Tennessee Hospitals lose $74.5 million 2015-2017.

Note due to overuse of Medicare, Medicaid, and uninsured are losing millions even before the Wuhan Flu. They are in a panic over Covid 19 due to a lack of intensive care beds and staff.

It is so bad they are begging retirees to come back to work. Most are refusing.

This problem can be traced to the same problems plaguing entire industries in this region: short staffing, under payed, over worked to the point of burn out. Dirty labor tactics.

When I taught community college I asked the head of the nursing program how long do nurses work. She said most quit after three years.

Same problem with nursing homes. Years of low pay has driven many to leave the region or retire. I know for a fact some have rehired fired drug users to fill positions. That is how bad it is.

Date July 17, 2021. The past 20 months of the Wuhan Flu crisis has affected little of Southwest Virginia. Our number of cases were never that high nor were deaths even with a large sick and elderly population.

The problem is and existed before is staffing shortages caused by the anti-worker, low wage business culture in this region.

Bristol Virginia for example with population of ~17,000 had a death rate of ~0.22%. The national rate assuming 338 million and 608,000 alleged dead 0.18%.

The reason I choose Bristol, Virginia/Tennessee as a focus point is its position on the Tennessee/Virginia state lines. It sits dead center of Southwest Virginia and East Tennessee.

Bristol Virginia sits in Washington County Virginia, Bristol Tennessee sits in Sullivan County Tennessee.

Washington County and Sullivan County are the wealthiest in the region. The surrounding counties are worse off. Even they are a joke when is comes to jobs and earning a real living. A lower cost of living only goes far with lower wage scales.

Bristol Virginia Job ad offering a $500 sign on bonus.

But as of September 2021 workers have finally made some gains after decades of losses. Or so it seems. Crap service jobs are begging for workers and offering as much as $13 an hour for jobs 2 years ago were paying $8.

The reality is most jobs still fail to get above minimum wage adjusted for inflation from 1971.

NOTE: Minimum wage in Virginia increased to $11 an hour on Jan. 1, 2022 and is set to increase to $12 next January.

But business

Virginia did raise minimum wage to $9.50 an hour in 2021, something they should have done in 2008. Raising it now is meaningless.

Employers across the region claim they can't hire skilled workers or workers at all. They have only themselves to blame.

They refuse to train or apprentice new workers - they demand taxpayers do it for them. Hell why not pay their salaries too?

Even then they refuse to commit to hiring them. They refuse to raise wages to attract workers - on average pay-scales across this region are 40-60% below the State average even for a college degree. Most won't hire college graduates to begin with - got to maintain social apartheid.

An insidious coalition of the Chamber of Commerce, state, local government agencies actively engaged in a campaign to keep wages low and working people powerless.

Dirty labor tactics such as constant hire-fire, temp agencies, etc. Even economic development agencies using millions in public money helped business engage in this behavior.

As I was informed by a government agency hack, "Business doesn't give a damn about your skills, education or experience. We are here a assist business, period."

That attitude is typical of the abusive, bastard employers and pseudo-government economic developers in this region.

The only jobs they created was their own. In fact local governments help setup non-profits in order to get grants, most were wasted.

For example I remember the Weldon Cooper Center in Wise, Virginia (part of UVa at Wise at that time) told me how they did (to me) a bogus study to for the purpose of obtaining millions in ARC and Tobacco grants for a country music museum in Bristol, Virginia.

I don't know of any prediction the Weldon Cooper Center has ever gotten right.

$12 million later, and it has been open several years, there have no measurable benefit to the people of Bristol. Note Fig. 1 above as proof. They refuse to give me a specific list of jobs they claim to have created.

As one ex-city official put it, "one can't go by job numbers" or something like that. Then how does one promise thousands of jobs but can't document any of them?

And that has been the problem all along. No oversight where the money went and no metrics to measure success by.

Yes I could use Virginia Freedom of Information Act to check the City or local government end, but that doesn't apply to grant recipients or economic development! They get the money, nobody knows where it went.

This is compounded by Virginia Laws such as executive or closed session. Any discussion on anything related to grants, government contracting, corporate welfare (incentives) etc. are barred from the public.

The press and public are locked out of the meeting, proper records are seldom kept, no recordings etc. allowed.

This is why ten people went to Federal prison over backroom dealing at Bristol Virginia Utilities.

This is why the Virginia Tobacco Commission that has wasted nearly $1 billion needs an extensive and public forensic audit.

This is how taxpayers lost tens of millions in various economic development scams such as The Falls ($100 million) or the Nicewonder fiasco at Exit 7.

No surprise those behind these deals soon disappear from City Government. In fact they often leave the community entirely.

This place is so messed up they gave away over $50,000 in electrical equipment to a Red Lobster restaurant - then stuck City utility customers with the bill.

Most of the endemic class warfare in the local culture became exposed for all to see. In the past nepotism was key to getting into any of the good jobs - even that didn't work.

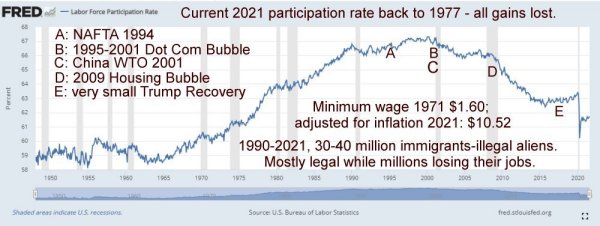

American Labor Participation Collapse.

For a larger view of above click American Labor Participation Collapse

The Lost Generation

The image above illustrates the destruction of American workers. NAFTA, China, speculation bubbles on Wall Street, and tens of millions imported workers as tens of millions of jobs disappeared.

This was government policy. Every American worker had a corporate-globalist bullseye on their backs. Corporatist government at its best.

For the last generation going back to 1990 an entire generation had no chance to get a decent job. They watched their mothers and fathers downsized and ruined.

Those entering the labor market had no real jobs, thus gained no experience or work ethic. Becoming a good worker means having real jobs to learn how to work and start a family.

The results are predictable: drug use, broken families, single mothers, etc. and millions leaving the labor force.

The 20,000 to 30,000 workers fired across this region have retired or moved on.

Business forced to compete against slave labor in Mexico and China treated their workers like third-world serfs.

That is why many even if qualified won't work for employers with a reputation for abuse and low pay.

It would have been far better to let markets operate properly, cut off mass illegal immigration, and stop paying businesses to locate out of the country.

America first even if one hates Trump.

The Bristol Herald Courier August 21, 2021 notes the following report from our Chamber of Commerce paid for by a $81,000 Government grant:

BRISTOL, Va. -- The Bristol Chamber of Commerce on Wednesday released a report detailing the Twin Cities' biggest challenges and opportunities for economic growth...The report cited an aging population, the "brain drain" effect of talented workers "moving away to seek better employment opportunities" and low wages as some of the area's top barriers to economic development...

No shit, the very things I documented here for over 20 years without a government grant to waste.

Their answer to the problem is the same garbage central planning of the last 20 years:

The report also recommended focusing on eight key issues to drive economic growth over the next 20 years: arts and tourism, the music economy, a competitive workforce, entrepreneurship, housing, leadership and collaboration, downtown Bristol and targeted business...

Already did that and it failed! They had a luncheon in the useless Bristol Train Station they wasted $6 million in grants "fixing up" then around another $600,000 to lobby AMTRAK to come to Bristol.

Sorry Bristol the proverbial train has already left the Bristol Train Station. Another wasted $81,000.

That is why government efforts to "fix" this region's economy was a waste of time even if we eliminated corruption and graft.

Federal policy favoring finance and foreign slave labor over producing real things here is behind these problems.

My advice for those staying out of the workforce to collect handouts is get a job, any job.

Get to work on time and do a good job. Show the employer you are really worth $13 an hour.

Learn self-sufficiency because the broken system won't save you.

Get out of debt, live within your means. If your employer fails one might not have government handouts to fall back on.

- 'Go Virginia' Scam More of the Same Government Waste 2018

- Bristol Virginia Tri-Cities a Great Place to Retire

- Three Decades of Job Losses in Southwest Virginia

- Bristol VA-TN Welfare State in 2004

- Town Halls and Other Controversy 2009

- Debating Issues in Bristol VA-TN in 2010

- Social Apartheid in Tri-Cities Bristol Virginia 2011

- Advantages of Social Apartheid in Bristol

- Bristol Virginia Social Apartheid Continues 2005-6

- Residents Flee Bristol VA-TN

- Sullivan County Tennessee Exposed 2012

- Social Apartheid Bristol, Virginia-Tennessee 2020

Science

The following are how history was altered by climate.

- Fall of the Late Roman Empire

- End of the Vikings in Greenland

- Lost Colony of Roanoke Island

- Whale Fossils Show Ice Free Arctic

Mass Failure of Government Economic Programs

With those in Washington thinking they can buy a new economy with government central planning and mass amounts of money need to come to our region to find out what NOT to do.

Indicative of economic life in Bristol was the collapse of the Tenneva Holiday Inn on State near downtown. This in my opinion shoddy structure is still unfinished as of November 2021. It was started in June 2019.

In 2016 Ball Container shuttered its Bristol Virginia plant firing ~220 workers. Some Chinese firm Merchant House International Limited got the building in December 2017. There was more hoopla "jobs", millions spent, 400 new jobs promised to make towels.

Local press reports that by December 2019 only 50 jobs materialized, zillions more predicted by 2020. As of Novenber 2021 little has come of this as I predicted. Perhaps turmoil in Hong Kong (the company is based there) or the Wuhan Flu set things back?

What is really stupid is to locate a textile plant in an area where nobody has ever worked textiles. Thus the damn lies begin again.

To

Yet ABC 13 in Lynchburg proclaims the headline, "Hong Kong-based company expands in Virginia, creating 405 new jobs...Governor Terry McAuliffe was in the City of Bristol Tuesday, announcing that more than 405 jobs have been created."

Where do they hire these reporters? That was a lie in 2017 and the story has never been corrected. This is among many of Governor Terry McAuliffe's failed announcements.

The press simply reprints press releases and never follows up on their own stories. They might be doing just fine, I called their contact number at (276) 285-3703 and waiting to hear back. Oddly I got a person and not a company.

Virginia Interment College closed in 2014. They got millions in Tobacco and other economic grants to develop a "tourism degree program." I looked into this and there is no evidence any such program ever existed. They got the millions and though "financial collapse, shrinking enrollment and lost accreditation" slams the doors. Money gone, no accounting again.

Then to quote,

Chinese entrepreneur Zhiting Zang acquired the lifeless former VI campus at auction in December 2016 and announced intentions to establish a school under the aegis of his U.S. Magis International Education Center in Flushing, New York.

They were supposed to open February 2021. Still nothing. The Bristol Herald Courier tried to get more information but, "There was no response to a request for more information." Been there done that for years. Did Mr. Zhiting Zang get government money?

The Bristol Train Station wasted $6 million in highway and economic development grants still sits empty 15 years later. They spent at least another $500,000 plus lobbying to bring AMTRAK to Bristol. Spend millions on a train station and no trains. Nothing again.

Our $12 million Country Music has been open several years. No evidence of any real impact on the economy. I drove by the other day and the parking lot was mostly empty. Perhaps the Wuhan Flu is keeping the millions of visitors away?

I could go on with this for hours. $100 million in energy research centers. Failed. Call centers collect millions in public funding as "technology jobs" open and close like clockwork.

Northrop Grumman opened up in Russell County Virginia in 2006 as part of a lucrative Virginia state contract. They claimed the "creation" of 1000 new high tech jobs. Never even came close.

They were so incompetent Morgan Griffith my present Representative tried to get the contract pulled according to press. They still insist they created 1000 new jobs that never existed and the facility has all but closed 2 years ago.

The Virginian-Pilot September 15, 2010 led with the headline, "State data debacle doesn't disappear." To quote,

House Majority Leader Morgan Griffith wanted to know whom to blame for weaknesses in the state's computer contract with Northrop Grumman...Virginia's leaders thought that by turning over their computer system to a private company, they could rid themselves of responsibility for a core government service that just happens to be indispensable to the functioning of every other government service. That dangerous assumption is directly responsible for the substandard service taxpayers now receive as well as the flawed contract that may prevent the state from collecting meaningful penalties from Northrop Grumman.

Again a typical backroom deal. I was blocked from getting information on this from Virginia. I attended their job fair and found the number of promised jobs and pay scales were a scam. The damn taxpayers even paid for the phony job fair!

Northrop Grumman was a defence contractor with no experience in telecom. The results anyone could predict. The press closed the article with this quote,

That's not good enough, and state leaders must insist that the taxpayers are fully compensated for lost productivity and aggravation...

Read the story from the Virginian-Pilot: State data debacle doesn't disappear.

For a list of related stories see Three Decades of Job Losses in Southwest Virginia.

Below is more proof and the last I'll write on this subject. Morgan Griffith is my congressman VA 9th. Phil Roe represents East Tennessee 1st and is retiring. They are worthless.

- Bristol Compressors Stabs Workers-Taxpayers in the Back

- ALICE in Poverty Land in Southwest Virginia

- Morgan Griffith, Phil Roe Betray American Workers

- Morgan Griffith Wrong about Volvo Trucks

- Illegal Aliens Hurt Poor Tennessee Workers

- Virginia Tobacco Commission Loses $1.1 Billion

- 400 New Jobs is Just 50 Jobs

- Why the Poor are a Goldmine

- The system, Income, and Education in Bristol VA/TN

- Where the Welfare Millions Go in Appalachia

Taxpayer waste $8 million Bristol Virginia Energy Research Center another empty building producing nothing. See Green Energy Boondoggle in Bristol Virginia and Biofuel Scams Wastes Millions in Virginia.

- Tri-Cities Labor Market Report 2011 & 2016

- Taxpayer Funds Wasted To Renovate St. Paul Hotel

- Gov. McAuliffe Clueless on Jobs But Not Pork

- ARC Virginia Grants Pork and Salaries 2015-16

- 30 Years of Failure in Southwest Virginia

- Exide to Rehire 40 Bristol Workers - Not After All

- Disability Still Big Business 2017 in Southwest Virginia

- Disability the Hidden Unemployment Program

- Bristol Trainstation 2017 Still Producing Nothing

- Appalachian Regional Commission a Waste

- Address Corporate Culture Before Handing Out Money

Update December 2019: One of the worst child abuse cases in Sullivan County is in the news again. See Baptist Preacher-Wife Sentenced to 179 Years

Also see 2007 Christian-Newsom Race Murders Rock Knoxville.

A gang of Blacks in Knoxville kidnapped, raped, and murdered a young white couple after a carjacking. The press was more interested in the Duke-Lacrosse hoax - the black whore that lied about the young men later went to prison for murder.

See 2007 Christian-Newsom Race Murders Rock Knoxville.

Another victim of a black criminal on parole. Yes - white lives matter too!

Female victims of black violence.

- Christina Eilman Rape Costs Chicago Police Millions

- 12-Year-Old Emily Haddock Murder

- Emily Haddock killers Get Plea Bargain

- 15-Year-Old White Girl Gang Raped at School

Religious Traditions

My interest in this subject is from a historical and philosophical viewpoint. This came from a controversy over the Ten Commandments being placed in local courthouses.

For the record I'm not a Christian or Jew but hold them no ill will. I believe in fact based science, not consensus based science.

There is a great deal of material on this site in regards to religion, in particular subjects related to rational monotheism and the Bible. Because Christianity was a product of the Hellenism Alexander the Great would be a good place to start taking another look. The later Roman Empire as such never "fell" in 479 AD, it merely changed form, a process going back a few centuries.

"We can not command religion, for no man can be compelled to believe anything against his will."

Why study the historical Jesus?

To quote a Christian:

Because our faith is based upon a historical figure for whom more evidence exists than for Julius Caesar. Christians, Jews, journalists, theologians, historians and skeptics all take an active interest in every archaeological or manuscript discovery that might shed light or doubt on the origins of our faith. We, too, must be armed with these facts to confirm our faith and equip ourselves with reasons for the faith we hold in order to answer enquirers (1 Peter 3.15). Jonathan Went

- Religious Syncretism

- Platonism and Christianity

- Demiurge Creator of the World

- Alexander, the Jews, and Hellenism

- Hellenistic Period After Alexander

- Allegorical Interpretation

- New Age Religion

- Demiurge Creator of the World

- Gnosticism Primer

- Zoroastrianism

- Christian Original Sin

- Christian Trinity

- Jesus the Man

- Pelagius Heretic was Right

- Apostle Paul Founder Christianity

- Apostle John

- John Calvin

- St. Augustine

- Martin Luther

- Unitarianism

- Christianity

- Judaism

- The Devil

- Deism

- Pantheism

- End Times

- Paganism

- Scientific Case for a Transcendent God

- In Defense of Classical Deism

- Islam Versus Deism

- Pelagius and why he was right

- Classical Deist' View of Religion and Its Application Today

- Were the Three Magi Zoroastrian Pilgrims?

- Biblical Monotheism and Persian Influences

- More Questions on Zoroastrianism for Comparison

- Zoroastrianism, Judaism from the Jewish Encyclopedia

- Why Jesus was not Zoroaster or Buddha

- Is the Resemblance Between Zoroastrianism and Judaism Coincidence?

- Hellenism Meets Judaism

- Judaism Versus Zoroastrianism

- What are we to believe?

- Under Judaism God Alone Does Good and Evil

- Problem of Original Source Material for Zoroastrianism

- Web Master

- Hobby Electronics

- Environmentalism

- US Constitution

- Religious Themes

- Archive 1

- Deism

- Gnosticism

- Apostle Paul

- Bristol VA/TN

- Why we should know John Calvin

- Egyptian-Christian Connection

- Judaism Meets Zoroastrianism

- Judaism Meets Hellenism and the Logos

"We can not command religion, for no man can be compelled to believe anything against his will."

Western concepts of God have ranged from the detached transcendent demiurge of Aristotle to the pantheism of Spinoza. Nevertheless, much of western thought about God has fallen within some broad form of theism. Theism is the view that there is a God which is the creator and sustainer of the universe and is unlimited with regard to knowledge (omniscience), power (omnipotence), extension (omnipresence), and moral perfection. Though regarded as sexless, God has traditionally been referred to by the masculine pronoun.

Concepts of God in philosophy are entwined with concepts of God in religion. This is most obvious in figures like Augustine and Aquinas, who sought to bring more rigor and consistency to concepts found in religion. Others, like Leibniz and Hegel, interacted constructively and deeply with religious concepts. Even those like Hume and Nietzsche, who criticized the concept of God, dealt with religious concepts. While Western philosophy has interfaced most obviously with Christianity, Judaism and Islam have had some influence.

The orthodox forms of all three religions have embraced theism, though each religion has also yielded a wide array of other views. Philosophy has shown a similar variety. For example, with regard to the initiating cause of the world, Plato and Aristotle held God to be the crafter of uncreated matter. Plotinus regarded matter as emanating from God. Spinoza, departing from his judaistic roots, held God to be identical with the universe, while Hegel came to a similar view by reinterpreting Christianity.

Issues related to Western concepts of God include the nature of divine attributes and how they can be known, if or how that knowledge can be communicated, the relation between such knowledge and logic, the nature of divine causality, and the relation between the divine and the human will.

Extract from God, Western Concepts of | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Web site Copyright Lewis Loflin, All rights reserved.

If using this material on another site, please provide a link back to my site.