Is agency's work to end Appalachian poverty done?

Critics of the Appalachian Regional Commission say many distressed areas left.

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS MAY 23, 2004

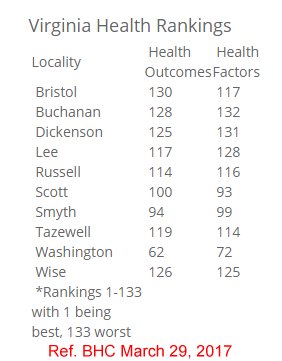

TweetThe Bristol Herald Courier opinion page on March 20, 2017 went into a rant titled "Trump ignored Appalachia" over cutting funding for the Appalachian Regional Commission. They claimed the number of high poverty (distressed) counties has been cut from 295 to 90. Yet the Associated Press on May 23, 2004 reported that the ARC had spent $10 billion over 40 years and "the number of counties in the region that are considered 'distressed' have been reduced from 223 to 91 since 1965." Then why if only 223 counties were "distressed" do we have 410 counties? Now we have 295 down to 90 in 2017? Which is it?

See

Bristol Virginia Region Exposed 2017

Growing Poverty Job Losses Tri-Cities VA-TN 2016

Growing Poverty Job Losses Tri-Cities VA-TN 2015

Nothing has changed in 2017. Below stands as a historical reference. See 30 Years of Government Failure in Southwest Virginia.

WASHINGTON - after nearly 40 years and almost $10 billion in federal spending, only eight of the 410 counties in Appalachia are equal to or better than the national average on indicators such as per-capita income, poverty and unemployment rates.

Some say that shows the agency dedicated to lifting Appalachia out of poverty has fallen short of its mission and focused too much of its resources on the region's most populous areas rather than its most distressed.

But Appalachian Regional Commission chairwoman Anne Pope says the eight so-called "attainment" counties only tell part of the agency's story.

She noted that the number of counties in the region that are considered "distressed" have been reduced from 223 to 91 since 1965. Those are counties with poverty and unemployment rates that are at least one-and-a-half times the national average.

"We've come a long way, but we have a little bit more to go," says Pope, who grew up in the Appalachian town of Kingsport, Tenn.

The agency was formed under President Lyndon Johnson at the urging of Appalachian governors in 1965, a year after the start of the War on Poverty.

The two crusades were separate but linked in their bid to eradicate poverty. While the War on Poverty became a national program, the Arc's focus has been exclusively on Appalachia.The commission defines the region as a 13-state area that loosely follows the spine of the Appalachian mountains from New York to Mississippi.

The governors of each of the 13 states help set the commission's policy and decide which projects to fund - a structure that some observers say is both a strength and weakness.

"ARC is such a political organization that it changes with the whim of politics," says University of Kentucky professor Ron Eller, an Appalachian scholar writing a book about the region. "A governor leaves and then a project gets de-funded."

Eller says the agency has made strides in recent years to focus on boosting homegrown businesses rather than just trying to lure industrial plant jobs, which tend to be low-paying and sometimes short-lived.

But he says the agency should be more strict about requiring regional planning in exchange for federal funds.

For example, he says the commission should look "holistically" at funding projects throughout targeted distressed counties to really make changes in those hard-hit areas rather than funding scattered pet projects all over the region.

Critics have opposed the commission's historical emphasis on aiding "the better off, more populous areas of Appalachia rather than the most distressed communities. Those are often rural and have greater needs but fewer people.

Examples of grants for urban projects that have sparked criticism include funding to lure an auto plant to Tuscaloosa, Ala., and build a football stadium in Spartanburg, S.C.

Ewell Bailtrip, a former representative to the commission from Kentucky says using ARC money to build the stadium in the relatively well-off community upset a lot of people.

"The question was why are we investing money in these centers that have their own economic dynamics?" Balltrip says.

Former ARC chairman Jesse White, who signed off on the stadium, says funding projects in the urban areas wasn't a mistake, but that not linking those urban centers into the surrounding, rural areas in a "thoughtful way" was a failure.

He noted the urban and suburban areas of Appalachia have been improved since the commission was formed. The eight attainment counties in the region are either urban or suburban. "The problem was it left the really isolated and distressed areas behind," White says of the old strategy.

In recent years, the commission's policy has been to spend 50 percent of the agency's money for economic development projects on distressed counties and areas. Pope says more than 60 percent of commission funding went to those communities last year.

In addition to funding economic development projects, the agency is building a new highway system throughout the region. The system is about 80 percent complete, and the agency spends about $450 million on it annually.

That's compared with about $66 million the agency spends yearly for economic development projects. ARC supporters say if the agency is falling short of its goals, a lack of money on the economic development side may be to blame. "Sixty-six million isn't a lot of money when you look at the federal budget," White says.

During the early years, the agency often got about twice as much as it gets now for economic development. But getting more money anytime soon appears unlikely.

Congress rejected a bid by White to boost the agency's budget by about $10 million to fund technology investments a few years ago. And the Bush administration attempted to cut the 2004 budget in half to a little more than $30 million.

Lawmakers from Appalachian states stopped that reduction, and the White House backed off when proposing next year's budget, but ARC supporters haven't been able to win new funding increases.

That effort has been hindered to some extent by competition from other agencies created in the ARC's image. The Denali Commission, which helps poor Alaskans, gets the most - $55 million annually in direct appropriations. But the Delta Regional Authority which aids the Mississippi Delta region, received just $5 million this year.

The Northern Great Plains Authority got even less, just $1.5 million. White says the fight over money will always be a problem. "I think the ARC always has to make the case to the rest of the country why it's important for them to fund this, he says. "In hard times it's a challenge to make that argument. Our argument was that until ARC finishes its job, these areas are a drain on the economy rather than adding to the economy."

Pope says she hopes there will be a time when Appalachia won't have to make its case, not because everyone will agree on funding but because the money won't be needed. "I long for the day when ARC will go out of business, when there is not a need for special assistance for the Appalachian region," she says.

See Growing Poverty Job Losses Tri-Cities VA-TN 2016

Growing Poverty Job Losses Tri-Cities VA-TN

- Why the Poor are a Goldmine

- Employment figures mask real truth 2004

- Some still fighting War on Poverty after 40 years

- Critics of the Appalachian Regional Commission say many distressed areas left

- Corporate welfare and Red Lobster for Bristol VA

- Less Welfare, Same Poverty in Heart of Appalachia

- Worlds Apart by Cynthia Duncan

- A Future Imperiled by Poverty

- How the ARC Wastes Millions

- Who Really Gets ARC Mountain Money?

- Poverty Myths

- War on Poverty and how the Poor Lost