Channing Interview

'2 October 1831. To-day I went see Mr. Channing, the most celebrated preacher and most remarkable author of the present time in America (in the serious style),' Tocqueville recorded in one of his diaries. It was their last evening in Boston; but they could not forego the opportunity of meeting the famous Unitarian divine. Their friend Joseph Tuckerman had secured the appointment for them.

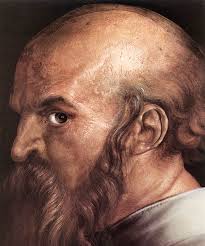

'Mr. Channing,' Tocqueville noted, 'is a small man, who has the air of being exhausted by work. His eyes, however, are full of fire, his manners warm-hearted. He has one of the most penetrating voices that I know. He received us with great kindness, and we enjoyed a long conversation, of which here are some parts:

'We spoke to him of how little religion existed in France, and he replied: I take the liveliest and constant interest in France; I believe that to her destiny is joined the destiny of all Europe. You exercise an immense moral influence round about you, and all the nations of the continent will follow you in the path you take. You have in your hands the power for good and for ill in a higher degree than any people that has ever existed. I am unable to believe that we must despair of seeing France religious; everything in your history gives witness that you are a religious people. And besides!

I think that religion is a need so pressing for the heart of man that it is against the nature of things for a great people to remain irreligious. I hope on the contrary that you will make the human species take a new step toward perfectibility, and that you will not, like the English, stop half way. They have stayed in the Protestantism of the 17th century; I am confident that France is called to the highest destinies, and will find a religious form still more pure.'

Here was Dr. Channing in a characteristic mood. Clearly he would have continued in the same vein for hours, had not Tocqueville and Beaumont finally take the bit in their teeth. 'I give myself full rein in the examination of religious question,' Beaumont later confessed to his family. 'I live only with Presbyterians, Methodists, Unitarians, etc. I break lances with them, in a way to persuade them that I am a warm Catholic; the truth is that I have never felt myself so attached to my religion as since the time that I have seen the aberrations of the other cults...'

At this point Beaumont and Tocqueville elected to discuss some of the most obvious objections to Dr. Channings's own faith. 'We spoke to Mr. Channing of Unitarianism,' Tocqueville's account pursued, 'and we told him that many people belonging to other Protestant sects had spoken to us of it with disfavour.

'The question between us, said Mr. Channing, is whether the 17th century can return, or whether it is past without return. They opened the road, and have the pretension to stop precisely at the point where the first innovator himself stopped. We, we claim to go ahead, we maintain that if human reason is steadily perfecting itself, what it believed in a century still gross and corrupted cannot altogether suit the enlightened in which we live.

'But are you not afraid, I said to him frankly, that by virtue of purifying Christianism you will end by making the substance disappear? I am frightened, I confess, at the distance that the human spirit has travelled since Catholicism; I am afraid that it will finally arrive at natural religion.

'I think that such a result, returned Mr. Channing, is little to be feared. The human spirit has need of a positive religion, and why should it ever abandon the Christian religion? Its proofs fear nothing from the most serious examination of reason.

'Permit me an objection, said I. It applies not only to Unitarianism but to all the Protestant sects, and even has a great bearing on the political world: Do you not think that human nature is so constituted that, whatever the improvements in education and the state of society, there will always be found a great mass of men who are incapable form the nature of their position of setting their reason to work on theoretical and abstract questions, and who, if they do not have a dogmatic faith, will not exactly believe in anything?

'Mr. Channing replied: The objection that you have just made is in fact the most serious of all those that can be raised against the principle of Protestantism. I do not believe, however, that it is without answer. 1. In the first place, I think that for every man who has an upright heart, religious questions are not as difficult as you seem to believe, and that God has put their solution within the reach of every man. 2. Secondly, it seems to me that Catholicism does not remove the difficulty; I admit that once one has admitted the dogma of the infallibility of the Church, the rest becomes easy, but to admit this first point, you have to make an appeal to reason. (This argument appears to me more specious than solid; but as we had but a limited time, I envisaged the question from another angle and resumed: )

'It seems to me that Catholicism had established the government of the skillful or aristocracy in Religion, and that you have introduced Democracy. Now, I confess to you, the possibility of governing religious society, like political society, by the means of Democratie does not seem to me yet proven by experience.

'Mr. Channing replied: I think that you mustn't push the comparison between the two societies too far. For my part, I believe every man in a position to understand religious truths, and I don't believe every man able to understand political questions. When I see submitted to the judgment of the people the question of the tariff, for example, dividing as it does the greatest economists, it seems to me that they would do as well to take for judge my son over there (pointing to a child of ten). No. I cannot believe that civil society is made to be guided directly byt he always comparatively ignorant masses; I think that we go too far.'

from Tocqueville and Beaumont in America, by George Wilson Pierson. Pages 421-3.

- Debunking Islamophobia

- Europeans Victims of (Muslim) Colonialism

- Deist Examination of Islamic Trinity

- Mohammed the Man as Islamic Ideology

- Why Muslims Can't Build a Lightbulb

- Bacon is not a Hate Crime

- Pedophilia Surrounds Afghan-Muslim Culture

- Myth of Early Islam

- Multiculturalism - Self-Liquidation of Europe

- Press Tries to Cover Up Muslim Violence

- Murdering Mother Hidden Face of Honor Killing

- Book Review Tom Kratman's Caliphate

- Who did what for Israel in 1948? America Did Nothing

- Palestine 1921

- Testimony of Arafat's Nazi Uncle in 1937

- Who is an Arab Jew? Albert Memmi

- Portraying Jews as 'White Europeans' Feeds Anti-Israel Agenda

- The Arabs in the Holy Land: Natives or Aliens?

- Controversy at Calvary Chapel

- Premillennialism and John Nelson Darby

- Comments From a Former Fundamentalist

- East Tennessee Strip Bar Wars

- Challenge to Atheists 1

- Challenge to Atheists 2

- Challenge to Atheists 3

- Challenge to Atheists 4

- Challenge to Atheists 5

- Original Sin an Overview

- Gnosticism as Explained by Bishop N. T. Wright

- Deist Critique of the Gospel of Mark

- Religious Syncretism and Christianity

- Classical Deist' View of Religion and Its Application Today

- Taking a Closer Look at Gnosticism and Christianity

- Thoughts on Theistic Evolution and Deism by Lewis Loflin

- My Answer to a Secular Fundamentalist by Lewis Loflin

- Notes on Neoplatonism

- Early Christian and Medieval Neoplatonism

- Plato's Trinity

- Jesus the Man

- Paganism Explained

- What's New Age Religion?

- Zoroastrianism

- Taking a Closer Look at Gnosticism and Christianity

- Gnosticism as explained by Bishop N. T. Wright

- Alexander, the Jews, and Hellenism

- More on Alexander the Great, the Jews, and Hellenism

- Hellenistic Period After Alexander

- Alexandrian Philosophy and Judaism - Jewish Encyclopedia

- Platonism and Christianity

- Allegorical Interpretation