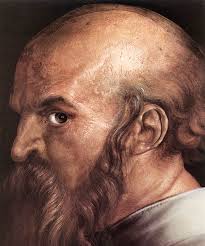

Arthur Koestler (1905-1983)

Hungarian born British novelist, journalist, and critic, best known for his novel DARKNESS AT NOON (1940), which reflects his break with the Communist Party, and his ideological rebirth. From 1937 Koestler was one of the main representatives of politically active European authors, whose attacks on the Soviet totalitarianism during the early period of the Cold War separated him from such internationally famous intellectuals as Sartre and Brecht. Since 1956 he focused on mainly in questions of science and mysticism, especially telepathy and extrasensory perception.

"All great works of literature contain variations and combinations, overt or implied, of such archetypal conflicts inherent in the condition of man, which first occur in the symbols of mythology, and are restated in the particular idiom of each culture and period. All literature, wrote Gerhart Hauptmann, is 'the distant echo of the primitive world behind the veil of words'; and the action of a drama or novel is always the distant echo of some ancestral action behind the veil of the period's costumes and conventions." (from The Act of Creation, 1964)

Arthur Koestler was born in Budapest as the son of Henrik K. Koestler,

an industrialist and inventor, and Adele (Jeiteles) Koestler. His parents

were Jewish, but later in 1949-50 Koestler 'renounced' his religious

heritage. As a businessman Henrik Koestler was unprejudiced - he financed

disastrous inventions like the envelope-opening machine and radioactive

soap.

In 1922 Koestler entered the University of Vienna (1922-26), and

became attracted to the Zionist movement. During this period he worked

with the revisionist, militant Zionist Vladimir Jabotinsky. Koestler left

for the Palestine in 1926 without completing his degree.

First he worked

as a farm laborer and then as a Jerusalem-based correspondent for German

newspapers. In 1929 he was transferred to Paris, a year later to Berlin

where he became science editor of Vossische Zeitung and foreign

editor of B.Z. am Mittag.

From 1932 to 1938 Koestler was a member of the German Communist Party, but left the party during the Moscow trials. He lived in France in 1932-36, earning his living as a free-lance journalist. Koestler traveled in the early 1930s Mount Ararat, Baku, the Afghan frontier, and Turkmenistan (then the Turkmen Soviet Republic), composing propaganda on Soviet progress. In Turkmenistan he met the American poet Langston Hughes, who later portrayed Koestler in his autobiography. In Paris Koestler edited the anti-Hitler and anti-Stalin weekly Zukunft.

During the Spanish Civil War Koestler was captured by the Franco

forces. The author had remained in Malaga after the military commanders

had fled, and he actually had no more duties as a correspondent. Koestler

spend his time under sentence of death in some kind of mystical passivity.

He used the library of the relatively luxurious jail at Seville and went

on hunger strikes.

It became apparent for the author, that he was an

exception among the prisoners - others were freely killed. In a message

three other prisoners, republican militiamen, wrote to him: "Dear comrade

foreigner, we three are also condemned to death, and they will shoot us

tonight or tomorrow. But you may survive; and if you ever come out you

must tell the world about all those who kill us because we want liberty

and no Hitler."

"Indeed, the ideal for a well-functioning democratic state is like the ideal for a gentleman's well-cut suit- it is not noticed. For the common people of Britain, Gestapo and concentration camps have approximately the same degree of reality as the monster of Loch Ness. Atrocity propaganda is helpless against this healthy lack of imagination." (from 'A Challenge to 'Knights in Rusty Armor'', The New York Times, February 14, 1943)

Finally the British Foreign Office managed to arrange for Koestler's

release. This period he depicted in SPANISH TESTAMENT (1937), rewritten as

DIALOGUE WITH DEATH (1942). From 1936 to 1939 he was a correspondent for

the News Chronicle. THE GLADIATORS (1939) was Koestler's first

novel. It dealt with the Spartacus slave revolt in Rome, one of the

favorite subjects of leftist writers from ancient history. In 1940

Koestler was arrested and interned in Le Vernet under the Vichy

government.

After his release Koestler moved to England, and wrote his

first book in English, THE SCUM OF THE EARTH (1941), an autobiography. He

served in the British Pioneer Corps (1941-42) and was employed by the

Ministry of Information and BBC. In 1945 Koestler became a British

subject. Koestler lived in North Wales three years and after the war he

traveled between England and the United States. In Suffolk he had a

farmhouse.

Koestler met Sartre in 1946 in Paris. Darkness at Noon, published in France under the title Le Zero et l'Infini was there a great success, selling over 400,000 copies, which annoyed the Communists. "I don't believe that my point of view is superior to yours, or yours to mine," Sartre later wrote, but they never became close friends.

Koestler made his international breakthrough as a writer with

Darkness at Noon. It depicted the fate of an old idealistic

Bolshevik, Rubashov, a victim of Stalin's rule of terror. Rubashov is

imprisoned in 1938 and persuaded to confess crimes 'against the state', of

which he is innocent. In his own mind Rubashov knows he is guilty of

working for system, that has cost too much suffering. "I no longer believe

in my own infallibility," he admits. "That is why I am lost." The book was

based partly on writer's own experiences a prisoner and on Stalin's

trials.

It revealed the totalitarian system and the decay of the Russian

Revolution. Darkness at Noon is considered one of the most powerful

political fictions of the century and it was adapted for the Broadway

stage by Sidney Kingsley in 1951. Among Koestler's other works about

Stalinism and Communism are THE YOGI AND THE COMMISSAR (1945) and THE GOD

THAT FAILED (1949).

In his memoirs, ARROW IN THE BLUE (1951) and THE

INVISIBLE WRITING (1954), Koestler analyzed his quest for Utopia and his

disillusionment with Russian communism."In the social equation, the value of a single life is nil; in the

cosmic equation, it is infinite... Not only communism, but any political

movement which implicitly relies on purely utilitarian ethics, must become

a victim to the same fatal error.

It is a fallacy as na�ve as a

mathematical teaser, and yet its consequences lead straight to Goya's

Disasters, to the reign of the guillotine, the torture hambers of the

Inquisition, or the cellars of the Lubianka." (from The Invisible Writing

From the 1950s Koestler published scientific and philosophical works.

He lived for a while in Delaware in the United States with his second wife

- his future third wife, Cynthia Jefferies, acted as his secretary. "A

gentle, soft, sad woman" described Duncan Fallowell her in his interview

of Koestler - the last he granted before his death. The author himself was

not at his best, he had a cold, and he answered shortly, except when he

was talking about the influence of his books.

"Look at

this. Did you ever see a magazine called the New Musical Express? It turns out there is

a pop group called The Police - I don't know why they are called that,

presumably to distinguish them from the punks - and they've made an album

of my essay "The Ghost in the Machine." I didn't know anything about it

until my clipping agency sent me a review of the record." (from Writers at Work, ed by George Plimpton, 1986)

In the preface to his book of essays TRAIL OF THE DINOSAUR (1955),

Koestler declared his literary-political career over. During 1958 and 1959

he traveled to India and Japan, in order to discover whether the East

could offer a spiritual aid to the West. For his disappointment, he did

not find what he was looking for and reported on his failure in THE LOTUS

AND THE ROBOT (1960). Koestler's article about Anglo-American 'drug

culture, 'Return Trip to Nirvana' appeared in Sunday Telegraph in

1967 and challenged Aldous Huxley's defence of drugs. He experimented at

the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor with psilocybin and combined its

effect to his vision to Walt Disney's Fantasia. "I

profoundly admire Aldous Huxley, both for his philosophy and

uncompromising sincerity.

But I disagree with his advocacy of 'the

chemical opening of doors into the Other World', and with his belief that

drugs can procure 'what Catholic theologians call a gratuitous grace'.

Chemically induced hallucinations, delusions and raptures may be

frightening or wonderfully gratifying; in either case they are in the

nature of confidence tricks played on one's own nervous system."

In the 1970s Koestler was made a Commander of the Order of the British

Empire and a Companion of Literature. Facing incurable illness -

Parkinson's disease and terminal leukemia - and as a lifelong advocate of

euthanasia, Koestler took his own life with his wife, who, however, was

perfectly healthy. Koestler died of a drug overdose - death was reported

on March 3, 1983.

In her suicide note Cynthia Koestler wrote, "I cannot

live without Arthur, despite certain inner resources."- Koestler was

married three times: Dorothy Asher (1935-50), Mamaine Paget (1950-52), and

Cynthia Jefferies (1965-83). He also had several affairs - but his one

one-night stand with Simone de Beauvoir in Paris was for both of them

something they did not want to repeat.

Throughout his life Koestler had psychic experiences, though he

maintained that he was not himself psychic, did not believe in "hidden

wise men in Tibet", and never met Gurdjieff or Aleister Crowley. He

established The Koestler Foundation, which exists to promote research in

parapsychology and other fields.

In his will Koestler left his entire

property to found a Chair of Parapsychology at the Edinburgh University.

Koestler's best-know scientific publications from the 1970s are ROOTS OF

COINCIDENCE (1972), an attempt to provide extrasensory perception with a

basis in quantum physics, and THE CHALLENGE OF CHANGE (1973), where he

related his study of coincidences to the 'synchronicity' hypotheses of Carl Jung and Kammerer, a zoologist

wrongly convicted of fraud because he seemed to have discovered an

exception to the rule, that acquired characteristics cannot be

inherited.

Selected works:

- SPANISH TESTAMENT, 1937 - abridged as DIALOGUE WITH DEATH, 1942

- THE GLADIATORS, 1939

- DARKNESS AT NOON, 1940 - Pimeaa

- THE SCUM OF THE EARTH, 1941

- ARRIVAL AND DEPARTURE, 1943 - Tuomion

- TWILIGHT BAR, 1945

- THE YOGI AND THE COMMISSAR AND OTHER ESSAYS, 1945

- THIEVES IN THE NIGHT, 1946

- THE CHALLENGE OF OUT TIME, 1948

- THE GOD THAT FAILED, 1949, ed. by R. Crossman

- PROMISE AND FULFILMENT, 1949

- INSIGHT AND OUTLOOK, 1949

- THE AGE OF LONGING, 1951

- ARROW IN THE BLUE, 1952

- THE INVISIBLE WRITING, 1954

- THE TRAIL OF THE DINOSAUR AND OTHER ESSAYS, 1955

- REFLECTIONS ON HANGING, 1956

- THE SLEEPWALKERS, 1959 - abridged as THE WATERSHED, 1960 - Vedenjakajalla

- THE LOTUS AND THE ROBOT, 1960

- CONTROL OF THE MIND, 1961

- HANGED BY THE NECK, 1961

- SUICIDE OF A NATION? 1963

- THE ACT OF CREATION, 1964

- STUDIES IN PSYCHOLOGY, 1965

- THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE, 1967

- DRINKERS OF INFINITY, 1968

- BEYOND REDUCTIONSM, 1969

- THE CASE OF THE MIDWIFE TOAD, 1971

- THE CALL-GIRLS, 1972

- THE ROOTS OF COINCIDENCE, 1972 - Parapsykologiaa vain yhteensattumaa

- LION AND THE OSTRICH, 1973

- THE CHALLENGE OF CHANGE, 1973

- THE HEEL OF ACHILLES, 1974

- THE THIRTEENTH TRIBE, 1976

- LIFE AFTER DEATH, 1976

- JANUS - A SUMMING UP, 1978

- BRICKS TO BABEL, 1980

- STRANGER IN THE SQUARE, 1980

From http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/koestler.htm

» Archive 1 » Archive 2 » Archive 3

» Archive 4 » Archive 5 » Archive 6

» Archive 7 » Archive 8 » Archive 9

- Taking a Closer Look at Gnosticism and Christianity

- Gnosticism as explained by Bishop N. T. Wright

- Alexander, the Jews, and Hellenism

- More on Alexander the Great, the Jews, and Hellenism

- Hellenistic Period After Alexander

- Alexandrian Philosophy and Judaism - Jewish Encyclopedia

- Platonism and Christianity

- Allegorical Interpretation