Purim: The dangers of deism

By Rabbi Yonason Goldson

Jewish World Review March 8, 2001

"Remember what Amalek did to you on the way, as you departed from Egypt: How they ... cut down the weak who trailed behind you, when you were faint and weary ... You shall erase the memory of Amalek from beneath the heavens. Do not forget." -- (Deuteronomy 25:17-19)

How is it possible that the Torah commands us to annihilate another nation? And if it does, how are we better than those peoples who have tried to exterminate us throughout our history? Why is the nation of Amalek singled out for this extreme sentence over all our other enemies and oppressors?

In its victory over Egypt, Israel acquired much more than its own freedom: it

acquired for the entire world a victory for moral order over moral anarchy, as

well as a victory for commitment to the community of mankind over self-serving

oppression.

By casting off the shackles of Egyptian domination and embracing its

Divine mission, the fledgling nation of Israel symbolized the lofty potential of

the human soul and the limitless capacity of human achievement.

This is what it means to be a "chosen people" - that even when other nations may shrink from the obligations implicit in their own humanity, the Jewish people remain committed to carry the banner high as a reminder to the world of the godliness that resides within every human being.

But it is no simple job serving as the moral conscience of the world. Indeed, many peoples have resented the Jews for setting so rigorous a standard. But only the nation of Amalek possessed such zeal to risk its very existence in hope of tearing down the banner and letting anarchy once again reign supreme.

It was not simply Amalek's attack upon the Jews - it was the manner of their

attack, how they cut down the weak who trailed behind.

In their opposition to moral absolutism, Amalek understands that the best

strategy is not frontal attack.

Far more effective is the steady chipping away

of what is right and what is good, the persistent prodding of civilized society

down one slippery slope after another, the philosophical erosion of values and

beliefs by promoting cynicism, double-standards, and equivocation.

In the language of contemporary theology, Amalek is a nation of deists,

asserting that the Creator resides in the heavens, that the human race resides

upon the earth, and that there is no interaction between them whatsoever.

It is an attractive belief, for it offers the comfort of a universe that is ordered

and purposeful, while at the same time eliminating any obligation to an ultimate

moral authority. In short, the philosophy of Amalek is nihilism masquerading as

spirituality.

Just as Amalek risked their lives attempting to destroy Israel in the desert, so

too did Haman the Wicked, viceroy to the king and descendant of Amalek, risk his

own life to exterminate the Jews in ancient Persia.

It was not enough for him to

dominate the Jews or rule over them, for the very existence of a Jewish nation

proclaims that man attains true greatness only by subjugating himself to a

transcendent purpose unalterably defined by the Highest Authority. The holiday

of Purim, therefore, celebrates not only Haman's downfall but a victory for all

mankind in its aspiration for spiritual accomplishment.

Today, we face Amalek not as a nation but as an ideology, an egocentric belief in relative truth and moral autonomy. And now, just as thirty three centuries ago, it is Amalek's ideology that leads individuals and whole communities to hold corrupt values and make destructive decisions. By remembering Amalek, we remind ourselves that we are never entirely safe from the seductive whisperings of subjective self-interest.

And when we have turned away from moral compromise to stare unblinking into the face absolute truth, then the insidious philosophy of Amalek will be erased forever from the collective memory of all mankind.

Rabbi Yonason Goldson teaches at Block Yeshiva High School and Aish HaTorah in St. Louis, and writes a regular column for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Copyright 2001, Rabbi Yonason Goldson

From a Judaism FAQ site. (edited) circa. 2001

What is God? How far are we allowed to go in asking this question?

Judaism (among other faiths) affirms theism - the belief in God. Since the dawn of rabbinic Judaism, the Jewish people have produced many of the world's greatest philosophers. Showing great intellectual courage, they met the question of "What is God?" straight on, and have produced a voluminous and inspiring literature that proposes answers to this question.

Not surprisingly, all of their efforts have been continually challenged by lesser minds, as many people are afraid that philosophical inquiry posed a threat to simple faith. When early medieval Jewish philosophers accepted Platonic philosophy as a way to help understand God, some responded with claims of heresy. When later medieval thinkers such as Saadya Gaon and then Maimonides accepted Aristotelian philosophy as a way to help understand God, some responded with claims of heresy.

Yet in all these ages, the spirit of rational inquiry prevailed. "Most medieval Jewish philosophers considered intellectual inquiry essential to a religious life, and were convinced that there could be no real opposition between reason and faith. Thus, Saadiah Gaon held that, 'The Bible is not the sole basis of our religion, for in addition to it we have two other bases. One of these is anterior to it; namely, the fountain of reason...' (Book of Beliefs and Opinions, 3:10).

Bahya ibn Paquda believed that it is a religious duty to investigate by rational methods such questions as God's unity, because, of the three avenues which God has given us to know Him and His law, 'the first is a sound intellect' (Hovot ha-Levavot, introduction; cf. 1:3)....This attitude toward the relationship between reason and faith dominated medieval Jewish philosophy. It reached its highest, most elaborate, and most familiar expression in the thought of Maimonides, and was reaffirmed by later philosophers, such as Levi b. Gershom and Joseph Albo. ["God", "in Medieval Jewish philosophy", Encyclopaedia Judaica]

How does theism differ from deism?

Judaism affirms theism as the basis for religion, as does Islam and Christianity. Beyond merely teaching that a god exists - which rules out atheism and agnosticism - Judaism specifically notes that only one god exists, thereby ruling out polytheism. God is conceived of as a creator and a source of morality, and has the power to intervene in the world in some fashion. The term 'God' thus corresponds to an actual ontological reality, and is not merely a projection of the human psyche.

Maimonides describes God in this fashion: "There is a Being, perfect in every possible way, who is the ultimate cause of all existence. All existence depends on God and is derived from God."

"Deism was still another conception of God that confronted Jewish theology. Deistic doctrine contains two main elements. First is the view that God, having created the world, withdrew himself from it completely. This eliminates all claims of divine providence, miracles, and any form of intervention by God in history. Second, deism holds that all the essential truths about God are knowable by unaided natural reason without any dependence on revelation.

The vast bulk of Jewish tradition rejected both deistic claims. It is hardly possible to accept the biblical God and still affirm the deistic view that he is not related to the world. Numerous rabbinic texts are attacks on the Greek philosophers who taught such a doctrine. Similar attacks continued throughout the history of Jewish philosophy.

Of the medieval philosophers, only Levi ben Gershom (Gersonides) seems to have had deistic tendencies." [Conceptions of God, Encyclopaedia Judaica]

On the other hand, Maimonides' rationalist interpretation may well be considered to be a bridge between deism and theism. "Maimonides' grandiose attempt at a synthesis between the Jewish faith and Greek-Arabic Aristotelian philosophy was received with enthusiasm in some circles, mainly of the upper strata of Jewish society, and with horror and dismay in others, imbued with mysticism and dreading the effects of Greek thought on Jewish beliefs.

The old and continuously smoldering issue of 'Athens versus Jerusalem' now burst into flames. Essentially the problem is one of the possible synthesis or the absolute antithesis between monotheistic revealed faith and intellectually formulated philosophy." [Maimonidean Controversy, EJ]

This is no doubt a reason why his "Guide of the Perplexed" became popular during the Haskalah movement. (Haskalah: Hebrew term for the Enlightenment movement/ideology which began in Jewish society in the 1770s.) "Haskalah, like its parent the European Enlightenment movement, was rationalistic. It accepted only one truth: the rational-philosophical truth in which reason is the measure of all things.

During the 1740s some of the youth had already begun to study Maimonides' Guide of the Perplexed. Haskalah accepted Enlightenment Deism, giving it a specifically Jewish turn. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, in the parable of the Three Rings in Nathan der Weise, rejected the claim of any religion to represent the absolute truth.

Mendelssohn held that there was nothing in the Jewish faith opposed to reason and that the revelation on Mount Sinai did not take place to impart faith but to give laws to a nation, because faith cannot be achieved by decree, while the laws which were given on that occasion were designed to serve as the laws of a unique Jewish theocratic state. Mendelssohn thus attempted to remove Judaism from the struggle between Enlightenment and revealed religion." [Haskalah, EJ]

The mainstream of classical Judaism affirms that God is personal. Adonai is a God that not only exists, but also cares about humanity. Rabbi Harold Kushner writes that "God shows His love for us by reaching down to bridge the immense gap between Him and us. God shows His love for us by inviting us to enter into a Covenant (Brit) with Him, and by sharing with us His Torah". One of the ways that we relate to God is through the many names of God; In Judaism, each of the many divine names is indicative of a different aspect of God's presence in our world.

(On the other hand, note that Maimonides rejected the idea of a personal God in this sense.)

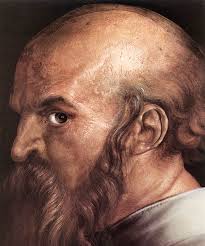

Moses Mendelssohn Jewish Deist

See Maimonides Versus Aristotle and the Jews of Spain, 13 Rules

» Archive 1 » Archive 2 » Archive 3

» Archive 4 » Archive 5 » Archive 6

» Archive 7 » Archive 8 » Archive 9